The Cold War and Children's Books

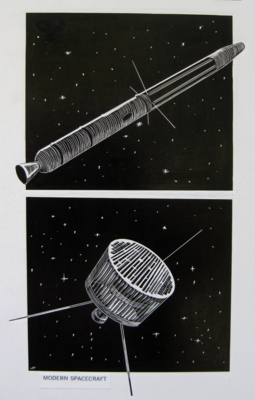

In 1957, the USSR successfully launched the first artificial satellite into space with its illustrious Sputnik 1 mission, triggering an avalanche of activity around the US space program and defense industry. One year later President Dwight D. Eisenhower passed the National Defense Education Act (NDEA), a government initiative designed to educate “the next generation of scientists.” The dominant perception of the time was that America’s children were woefully behind their Soviet counterparts, and only by actively promoting cutting-edge science throughout pedagogy and culture would we stand a chance of winning the Cold War. Science and technology became pervasive themes in American children’s literature and education, covering a wide range of subjects, including atomic energy, space travel, astronomy, and physics.

Children’s literature authors and educators came from a wide range of complex backgrounds. At the close of World War II, a covert government program called Operation Paperclip brought in former Nazi scientists and engineers from Germany to work on US space initiative and weapons development. In a fascinating twist of profession, Operation Paperclip rocket scientist Wernher von Braun and physicist Heinz Haber were commissioned to work on rocket science as well as develop children’s stories and textbooks, often in collaboration with Walt Disney. Both von Braun and Haber were central in promoting the importance of science to a broader audience. In a now famous 1952 Collier’s magazine article, Wernher von Braun made the case to the American public that the space program was vital work. Playing to the pervasive fear of Communism, he wrote that “a man-made satellite could be either the greatest force for peace ever devised, or one of the most terrible weapons of war—depending on who makes and controls them.” In 1957, Heinz Haber partnered with Walt Disney on Our Friend the Atom, a television show and children’s book extolling the virtues of the atom as a peace-keeper and potential energy source to get us into space.

The McCarthyism movement of the 1950s also impacted American children’s literature. Teachers and artists were being interrogated and blacklisted as Communists, often losing their livelihood and professional reputation. Irving Adler (pen name Robert Irving) was amongst those blacklisted, and was fired from his position as a high school teacher in New York City in 1951. Ironically, he garnered a much wider audience for his “radical” ideas through writing children’s literature and textbooks, as a massive influx of government funding went into developing educational resources in the sciences in an effort to fight the Russians.

This exhibition explores these fascinating and complex intersections between government, education, and children’s literature during the Cold War era.