The Guild of Women Binders

Rumblings of thought during the latter portion of the nineteenth century in Great Britain insinuated the degradation and disintegration of integrity in design and manufacturing. The founders of the Arts and Crafts Movement, a response to this perceived degradation, were opponents of the Industrial Revolution who sought a return to the beauty and careful craftsmanship inherent to medieval and gothic design. The philosophical bases guiding the Arts and Crafts Movement were nestled in the works of A.W.N. Pugin and John Ruskin. Pugin criticized the British Industrial Revolution and, like Ruskin, idealized gothic/medieval techniques as key exemplars for workmanship and design. A fellow theorist of Ruskin, William Morris is credited with founding the British Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris shared in the philosophical leanings of Pugin and Ruskin; he condemned the inherent trend industrialism had wrought upon manufacturing – the creation of a severance between designer and manufacturer (Obniski, 2008). Part of Morris’s monumental influence on Arts and Crafts aesthetic rested in his keen interest in typography and the craft of bookbinding (Art Story Foundation, 2020). He established the Kelmscott Press in 1891in order to create “beautiful” books in what was to be a fervent revitalization of bygone techniques in typography, illumination, binding, and the selection of materials for production.

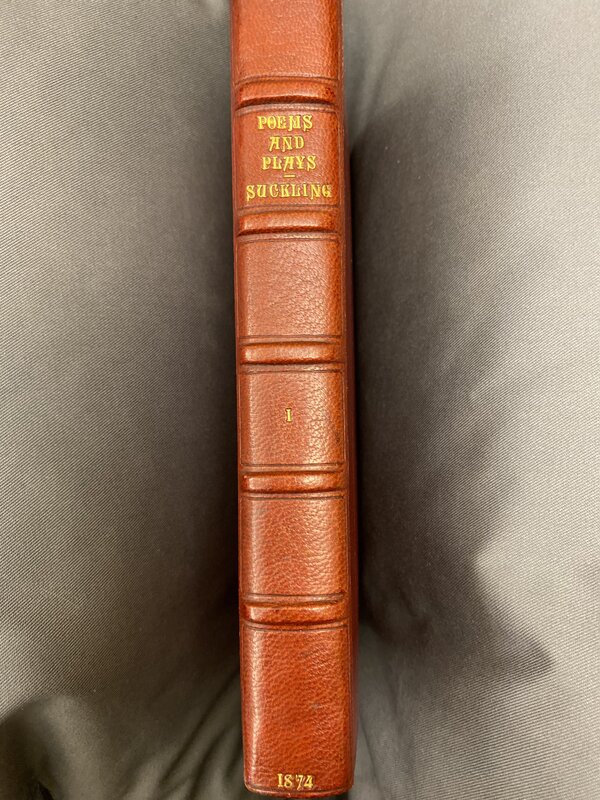

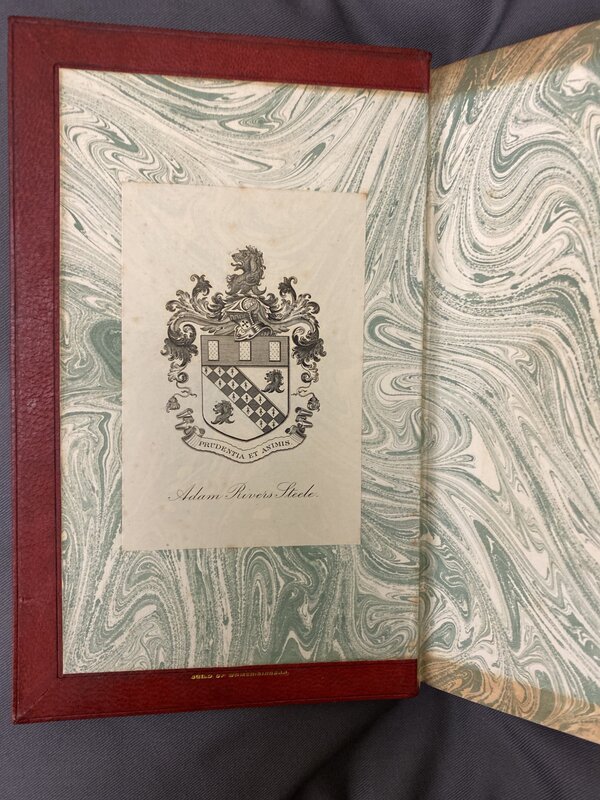

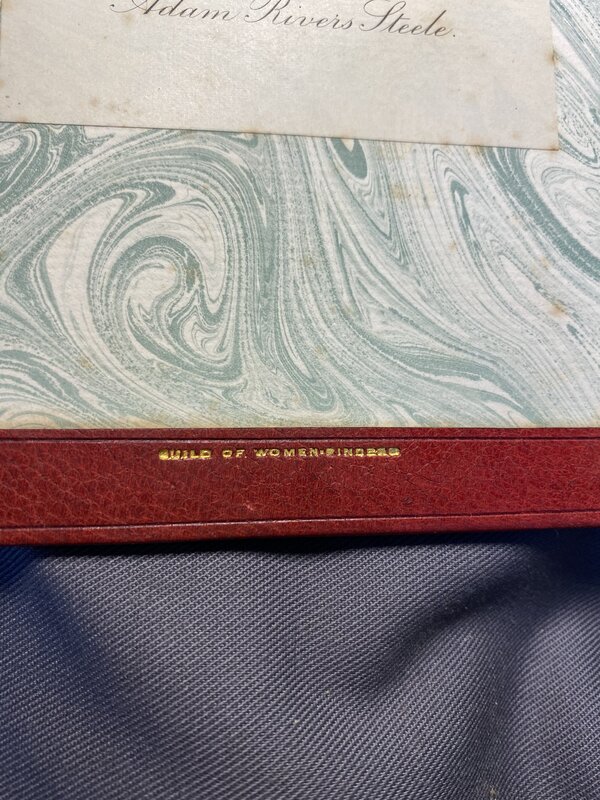

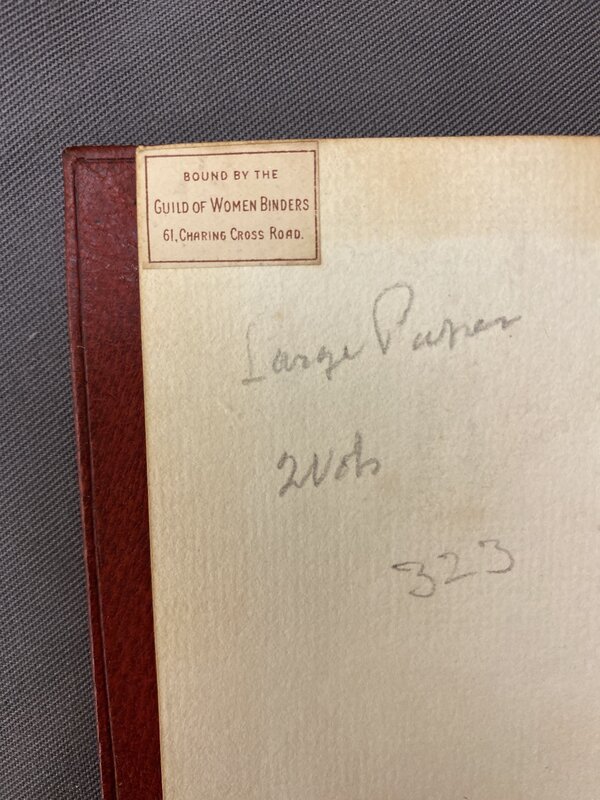

Tied inextricably to the Arts and Crafts Movement and to the ideals of William Morris and associates, Frank Karslake, an antiquarian bookseller from London and financial supporter of the Hampstead Bindery, promoted an exalted platform upon which the bookbinding craft of women shined. In 1897, Frank Karslake attended the Victorian Era Exhibition at the Diamond Jubilee honoring the Queen. Karslake keenly observed the unique binding work of Annie S. MacDonald, her pupils, and other women binders, and he discerned the inherent worth in the women’s approach to binding. The binding work of the women eschewed the degradative tendencies recognized by Morris, and favored design, embroidery, painting, and modelled leatherwork (Tidcombe, 1996). The artistic nature of bookbinding achieved a revival, and women were sought far and wide to study in schools and organizations of varying handicrafts, some of which included The Guild of Handicrafts, St. George's Guild, and the Chiswick Art Workers Guild (The Oak Knoll Biblio-Blog, 2020). In response to his revelatory observations at the Diamond Jubilee, Karslake gathered a constituency of women binders for an exhibition at his shop in Charing Cross, London, entitled “The Exhibition of Artistic Book-bindings by Women.” The event proved penultimate to the creation of the Guild of Women Binders in May 1898 (Cooke, 2018). Many of the women of the Guild of Women Binders emerged from the Chiswick Art Guild and the Chiswick School of Arts and Crafts, a craft school unique in its dedication to the availability of education for women in bookbinding. Karslake, a man of keen business intuition in the bookselling industry, discerned the lucrative opportunity teaching women to bind books potentiated, as the profits yielded far surpassed profits from his binding and selling alone. Karslake's Hampstead Bindery served as a transformative place for the cultivation of stellar design and binding produced by women (Tidcombe, 1996).

While the Guild of Women Binders originally grew from Ruskinian and Morrisian principles of the Arts and Crafts Movement, the Guild brought to the Movement a presence of empowerment for women - the opportunity for women binders to excel in their craft, to have independent and gainful employment with a living wage, and to have a creative outlet to express individual artistry (Cooke, 2018). Interest in bookbindery by women was ubiquitous across all demographics in terms of location and of economic and social class (Tidcombe, 1996).

The First World War effectively brought a withering end to the Guild of Women Binders, and bookbinding practices by women diminished as a whole. Other demanding areas of attention and action arose for women with the inception of the War. However, a select few women binders subsisted through the War, and post-war France boasted a small constituency of lingering women binders (Tidcombe, 1996). The golden age of women binders peaked just prior to the War, and though the Guild’s lifespan was brief, their legacy remains transcendent.