Greeks and Romans

Aristotle was the first to attempt a system of animal classification, in which he contrasted animals containing blood with those that were bloodless. Of all the works of Aristotle that have survived, none deals with what was later differentiated as botany, although it is believed that he wrote at least two treatises on plants.

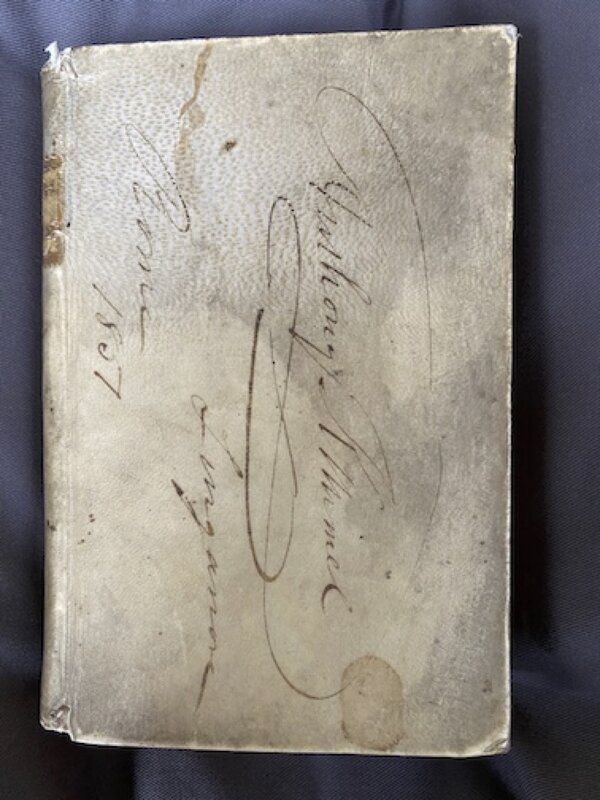

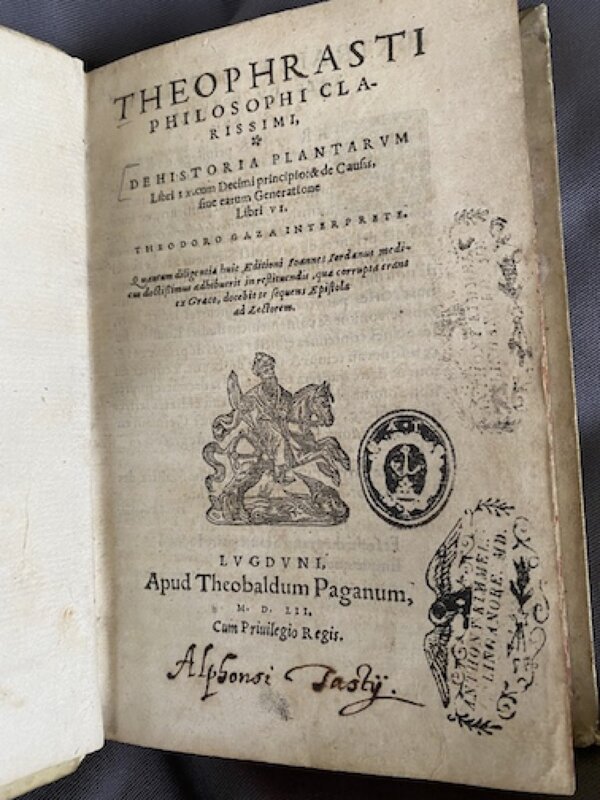

The work of Theophrastus (371-287 BC), one of Aristotle’s students, has been preserved to represent plant science of the Greek period. Like Aristotle, Theophrastus was a keen observer. In his great work, De historia et causis plantarum (The Calendar of Flora, 1475), in which the morphology, natural history, and therapeutic use of plants are described, Theophrastus distinguished between the external parts, which he called organs, and the internal parts, which he called tissues. This was an important achievement because Greek scientists of that period had no established scientific terminology for specific structures. For that reason, both Aristotle and Theophrastus were obliged to write very long descriptions of structures that can be described rapidly and simply today. Because of that difficulty, Theophrastus sought to develop a scientific nomenclature by giving special meaning to words that were then in more or less current use; for example, karpos for fruit and perikarpion for seed vessel.

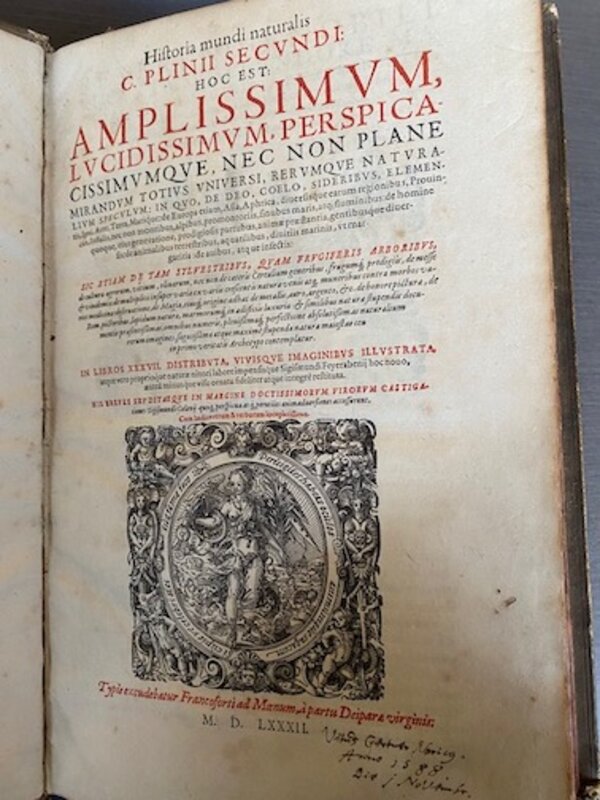

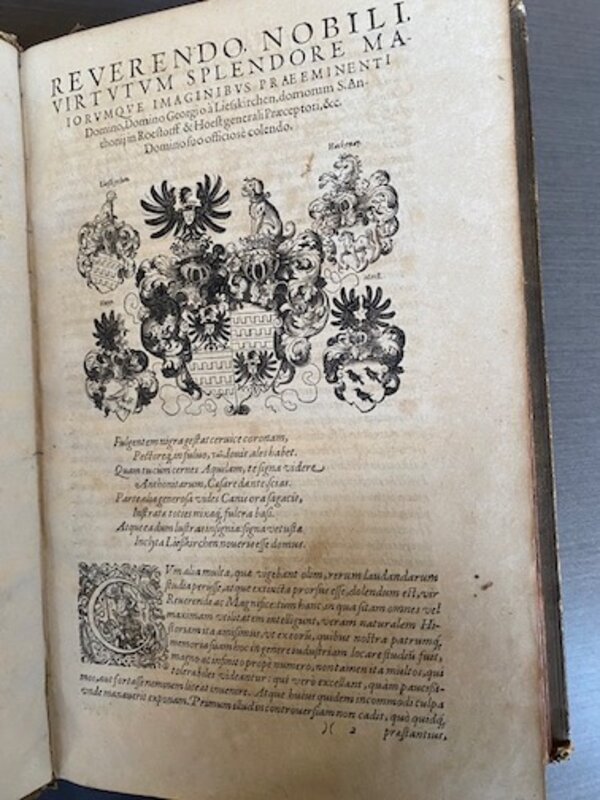

Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) wrote Naturalis Historia, in 37 books, and was completed in AD 77. Natural History is one of the largest single works to have survived from the Roman Empire and was intended to cover the entire field of ancient knowledge, based on the best authorities available to Pliny. He claims to be the only Roman ever to have undertaken such a work. It encompasses the fields of botany, zoology, astronomy, geology, and mineralogy, as well as the exploitation of those resources. It remains a standard work for the Roman period and the advances in technology and understanding of natural phenomena at the time.