Life Beyond Work

Community life helped sustain many minority groups in the face of adversity. Communities offered common cultural values, a shared language, family networks, an understanding of the hardships imposed by racist laws and attitudes, and some security. Entertainment sometimes offered bridges between cultures, and athletic prowess could be admired despite gender or race.

In Pendleton, Chinese immigrants developed a system of underground tunnels that allowed them to conduct business and life independently of white residents, and gave them haven after curfew. Other communities lived in more conventional settlements. In 1942, the town of Vanport was built on the south bank of the Columbia River to house the influx of wartime shipyard workers, many of whom were African-American. In 1948, a flood eradicated Vanport, and many of its residents relocated to the Albania district of Portland.

Minority civic life and leisure activities often paralleled that of white communities, without coming into much direct contact with them. Black churches such as Portland’s Bethel A.M.E. Church were hubs for the African-American community, providing social and spiritual support for their members. Fraternal lodges such as the Elks and Odd Fellows organized African-American chapters, some with women’s auxiliaries. Women’s clubs practiced traditional handicrafts, performed music, and nurtured political influence. The Chinese community operated a theater in Portland, performing traditional Chinese music and opera, and coming into conflict with white lawmakers over noise regulations. African-American baseball teams played as independent clubs until the Negro National League formed in 1920.

Japanese and Japanese-Americans in Oregon made concerted efforts to merge smoothly with white society, in part by forming associations to provide cultural leadership. The Japanese Association of Oregon and the Portland-based Japanese American Citizens’ League both developed early in the twentieth century and fostered cultural integration. The Portland YWCA became a popular site for American-born Japanese girls and women to participate in cultural programs with both minority and white peers. Even after their relocation to Oregon’s relocation camps in 1942, Japanese and Japanese Americans maintained a strong community infrastructure. Many camp residents organized and published newspapers as a means of preserving their voice and documenting their experiences. A collection of these newspapers is available from Knight Library's Microforms Department.

Minority communities often developed their own newspapers. The Advocate, published 1903-1933 in Portland, was one of the African-American newspapers, used by its editors—including Beatrice Cannady—to promote business and advocate for political activism. Newspapers offered news from the home nation for immigrants, provided conduits for social, educational and legal information, and helped organize for change. Above all they gave a voice to communities ignored by general newspapers. Many of these historic community newspapers have been lost or survive only in scattered issues.

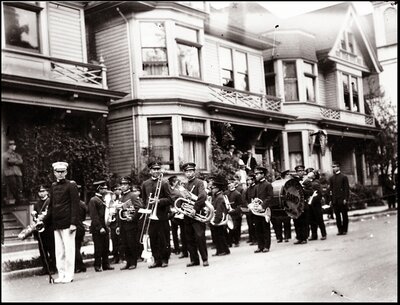

The Tigers

The Tigers, Pendleton's African-American baseball team, circa 1915-1917. Little is known about this team, chronicled in a few photographs and in brief reports in the East Oregonian. In 1911 a team called the Tigers lost to the Round-ups. The later Tigers played against other African-American teams such as the Walla Walla Giants, teams of unknown constitution including the Moose Paps and the Pilot Rock Pirates, and beat the Umatilla Indians, the tribal players from the Umatilla Reservation, in 1916. Following that game they issued a challenge to all comers, but lost to the Pendleton All-Stars (2-10) on Memorial Day in 1917.

The color barrier in baseball was established in the 1890s, following two decades of integrated play. By 1900 professional African-American teams were flourishing in the US, entertaining the black urban populations. The first Negro National League was founded in 1920, and the segregated leagues hosted great players and stunning competitions through World War II. Baseball began to reintegrate in 1946 when Jackie Robinson was signed by Branch Rickey for the Dodgers.

The 1915 Tigers roster:

Henry Hobson, manager

C. Wright, C,

E. Wright, P,

B. Hickman, SS,

Perkins, 1B,

G. Allen, 3B,

[Dick] Thomas, CF,

Jones, 2B,

Pollard, RF,

Hooker, RF,

Butler, LF.

The 1916 roster:

G.W. Hooker [listed as contact]

E. Wilson, LF,

Nixon, 3B,

Hickman, 2B,

Cranshaw, P,

C. Wright, C,

Vincent, SS,

E. Wright, 1B,

Dick Thomas, CF,

B. Hopkins, RF.

[Information from the East Oregonian (various dates) and Negro League Baseball, www.negroleaguebaseball.com.]

Parson Motanic

Parson Motanic (1863?-1950), showing his new car to Pendleton in 1915. Motanic was a member of the Cayuse tribe, and the second Native American on the Umatilla Reservation to purchase an automobile. In this pair of photos he poses in a traditional headdress and as a prosperous farmer. The passenger in the front seat is identified as the son of the salesman. The family members in the back seat are: Mary (not visible), Dorothy, Dan, Esther, Art, and Sarah Motanic.

In the early 1900s, Motanic was considered the leader of the wildest bunch of young bloods on the Umatilla Reservation. There was no man of the three tribes who could run as fast, who could dance as gracefully, who could ride as skillfully or who could compare with him in any feat of strength or skill. Known for his strength and his athletic prowess at football, Motanic's reputation was enhanced when he tossed a famous professional wrestler out of the ring in a local contest.

About 1908, following an all-night spree, Parson Motanic heard a sermon by Rev. J.M. Cornelison of the Pendleton Mission, and quit his life of idleness. The former athlete and dancer became a successful farmer and respected Presbyterian churchman. At one time he was one of the largest property owners of the Umatilla Reservation. In 1926 his daughter, Esther Motanic Lewis, became the first Native American woman to be named Queen of the Pendleton Round-Up. His son Art was active in the Round-Up for about seventy years, and was a well known singer at the Happy Canyon pageant. He also represented tribal and community interests.

[Information from articles in the Oregon daily journal, Apr. 16, 1915 and East Oregonian, Mar. 11, 1950, supplied by Pendleton Public Library.]