The New Century

The 20th century saw many changes in how Oregon treated its minority workforce. A state constitutional measure banned African-Americans from owning property in Oregon in 1857; it was finally repealed in 1926, and voting rights provided in 1927. This opened the way for black businesspeople to settle more freely in the state. Shipyards attracted African-American workers during World War II, and many of them settled in the city of Vanport. By 1950, African-Americans made up 2.6% of the state’s population.

Chinese workers also gained greater freedoms in Oregon’s 20th century, although not without setbacks. The 1859 Oregon Constitutional measure that prevented Chinese residents from voting was repealed in 1927. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed in 1943, allowing Chinese workers to live and work in the state. In 1946 the Oregon Constitutional measure preventing Chinese workers in Oregon from owning property or mining claims was repealed. Early Chinese professionals in Oregon included Seid Back, Jr. (1878-1933), the first Chinese lawyer admitted to the U.S. bar.

Japanese workers in Oregon suffered considerable racism during the early years of the 20th century, due in part to racial anxieties during wartime. In 1942 123,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans were moved to “relocation camps” on the West Coast. Over 4,000 were from Oregon. Following their release at the end of the war, Japanese Americans continued to meet with racial prejudice and hostility, and many had difficulty resuming their previous lives and recovering their property.

The Oregon Senate passed the Oregon Fair Employment Practices Act in 1949, but non-white Oregonians continued to have to fight for equality in the workplace.

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, commonly known as Jackson Sundown (1863-1923), nephew of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce. As a young man Sundown lived through the 1877 war against the Nez Perce, and spent several years in Canada in the camp of the Lakota chief, Sitting Bull. Although he lived in Montana and Idaho, Sundown was a familiar figure in Pendleton. He was so skilled at rodeo that others refused to compete against him, and he tamed some of the fiercest bucking stock on the rodeo circuit. Rodeo is a unique sport in that it grew directly from contests of skill by working cowhands.

Sundown became a legend in 1916, the year this picture was taken, coming out of retirement to win the world's rough-riding competition and the all-around championship at the Pendleton Round-Up at the unheard-of age of 52, twice the age of any of the other competitors. He was the first Native American to win a rodeo championship, and the support of the crowd at that event helped convince the judges to end the practice of denying wins to people of color. In 1972 he was inducted into the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame, and in 1976 he became the first Native American in the Rodeo Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy Museum.

George Fletcher

George Fletcher (1890-1971) at the Pendleton Round-Up, circa 1910. Born in Kansas, Fletcher grew up in Pendleton and was essentially adopted by a minister on the Umatilla Reservation. He became an unofficial member of the tribe, speaking Chinook and learning horsemanship from tribal elders. At a rodeo in Pendleton in 1909 he took third prize. He missed the first Round-Up the following year, having been jailed for "riding on the sidewalk" on a fractious bronc downtown. Sheriff Til Taylor then enrolled Fletcher for law enforcement, deputizing him as the sole member of the posse.

Known as a skilled horseman, George Fletcher gained lasting fame in 1911. Competing against Jackson Sundown and John Spain, the judges awarded the top prize in the bucking contest to the white man, despite the crowd's furious support for Fletcher. Sheriff Taylor cut up Fletcher's hat and sold the pieces to the crowd as souvenirs, raising enough money to buy a matching Hamley prize saddle for George Fletcher. A photograph of the three riders in the 1911 Round-Up (one African American, one Native American, one white) was the inspiration for Ken Kesey's novel, Last Go Round.

Miguel "Mike" Morales

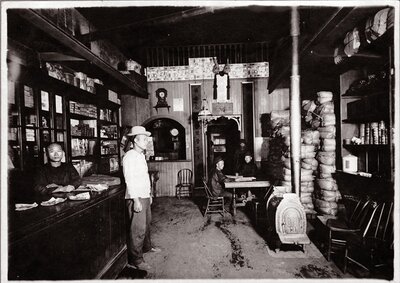

Miguel "Mike" Morales, famous bit and spur maker, Pendleton, circa 1912. Morales moved to Pendleton in 1910 and established a bit shop within the store of the noted saddlery, Hamley & Company, which for many years supplied the trophy saddles at the Round-Up. (This is an alternate version: the image exhibited was the same shown in the poster, with Morales seated in doorway, PH036-1499.)

He set up his own shop in Portland several years later, and worked there until moving to Los Angeles around 1925. His wife, Lena, remained in Portland. Morales' silver craftsmanship and original designs were highly regarded, and are now considered collector's items. [Information from Polk's city directories and the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.]