Women Workers

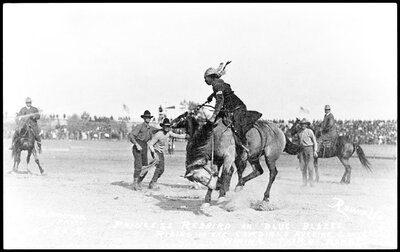

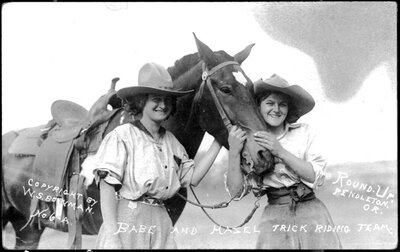

Oregon’s early economy strongly favored male workers, in industries ranging from mining to cattle ranching to forestry. Some women found work in these fields, despite the challenges. “One-Eyed Charlie” Parkhurst, a stage coach driver who died in 1878, was found after “his” death to have been a woman. “Little Joe” Monahan, a ranch hand who died in 1904, was also discovered to be female.

As Oregon’s social infrastructure developed, women made inroads in many professions. Bethenia Owens-Adair (1840-1926) earned a medical degree from the University of Michigan in 1880, and became the first woman physician in Oregon. 1886 saw the first woman admitted to the Oregon bar, Mary Gysin Leonard; it was not until 1922 that an African-American woman, Beatrice Cannady, was admitted. Minnie Hill took the helm as Oregon’s first female steamboat captain in 1886.

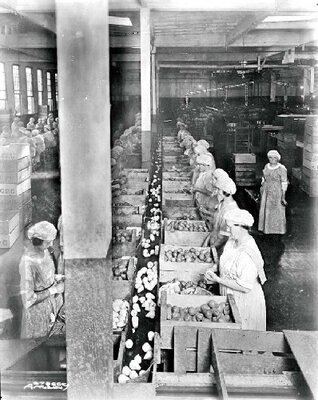

More usual occupations for women in Oregon were those of missionary, schoolteacher, governess, and homemaker. Later, women found work in factories, offices, and the armed forces. When male workers returned home to Oregon from World War II, women were expected to relinquish their jobs in order to provide positions for men. Many women preferred to continue working outside of the home, and fought to hold their jobs or seek new employment. Unequal pay and barriers to promotion were common problems. The eight-hour work day for women was approved in 1914.

Employment opportunities for women who were also ethnic minorities were more constrained than those for white women. In many ethnic communities, women and children arrived only after the man had established a stable home. Even in communities where minority women could readily seek work, they often encountered greater obstacles than their white co-workers. Black female shipyard workers were frequently kept in entry-level positions while white women were promoted. At the turn of the century, the Portland Laundry Workers Union refused to allow black women to become members; the Portland Teamsters Union and Cooks and Waiters Union were also restricted to white members.

Women gained power slowly in Oregon. White women gained the right to vote in 1912, sixteen years after the women of Idaho, and only eight years before national suffrage.