Unveiling Tiptree: 1976-1987

The Women Men Don’t See: James Tiptree, Jr. Unveiled to the Science Fiction World

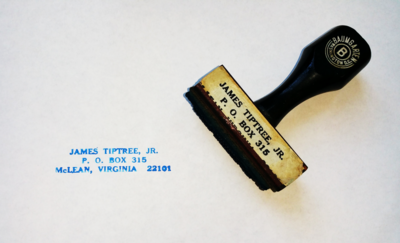

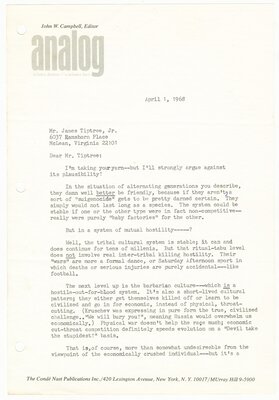

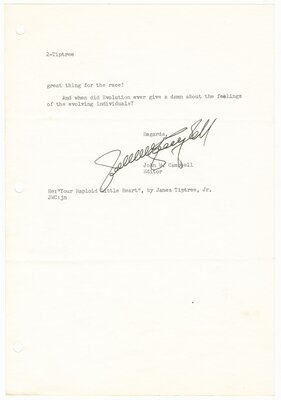

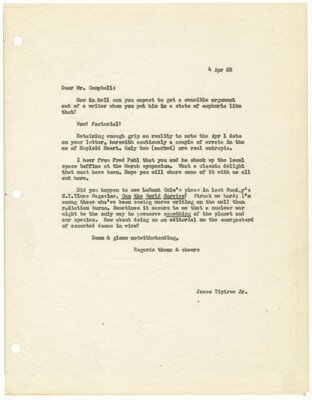

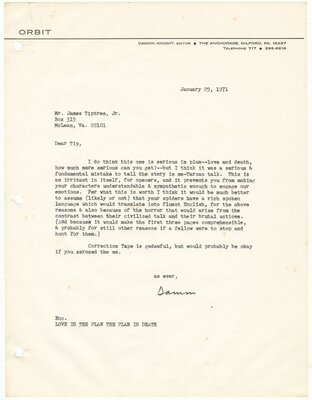

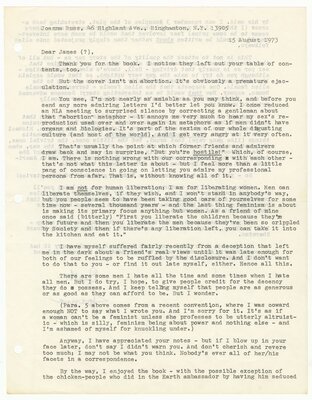

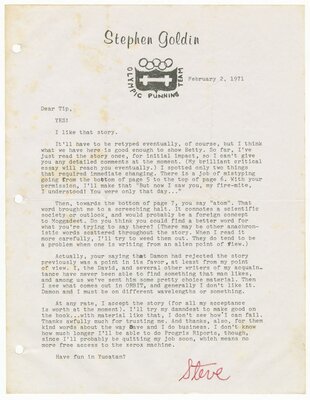

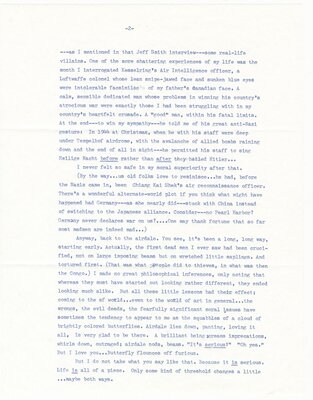

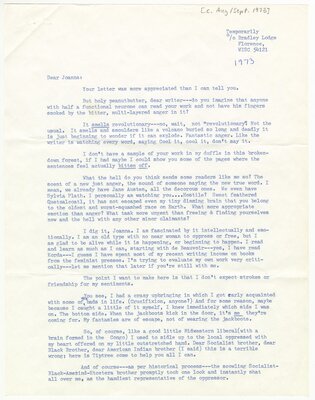

In the late 1960s, James Tiptree, Jr. began writing urgent and original stories, winning prestigious awards, and developing epistolary friendships in the science fiction world. His colleagues suspected that “Tiptree” was a pseudonym, but nobody had seen the notoriously private author in person.

Then, in October 1976, Tiptree told some friends that his mother had recently died. Curious, a few people looked up the obituary in Chicago papers, and it became clear that the author could be only one person.

Word spread quickly through science fiction circles: the “ineluctably masculine” James Tiptree, Jr. was in fact a sixty-one-year-old woman, Alice B. Sheldon.

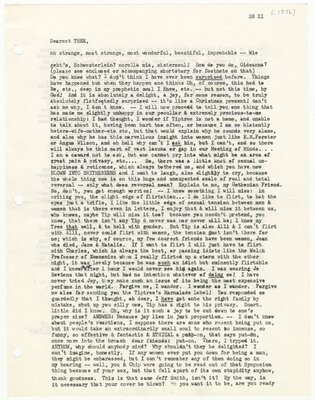

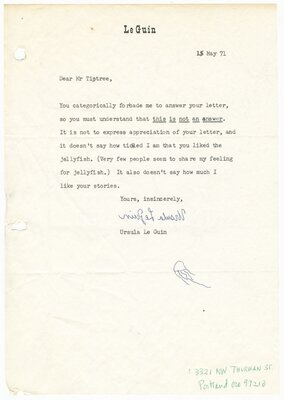

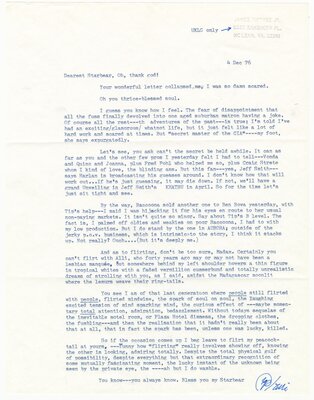

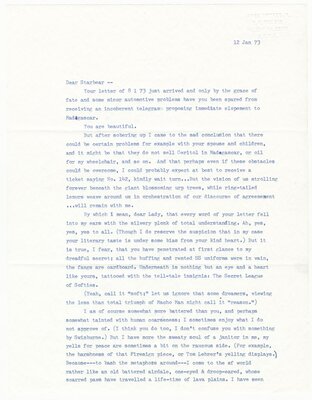

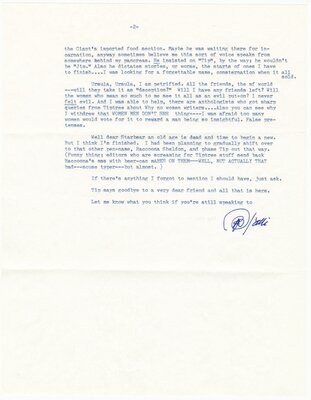

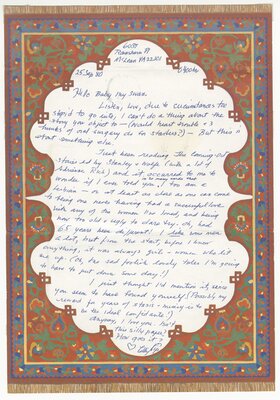

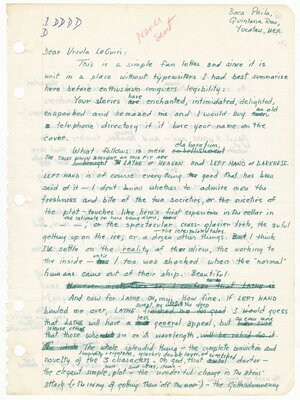

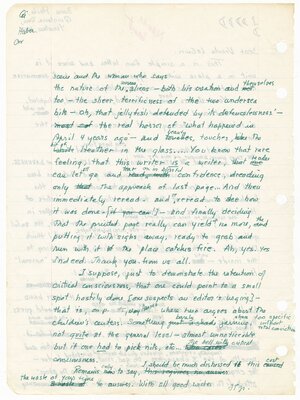

In a letter to Ursula K. Le Guin, Alice confessed her true name and gender to the writer who had become one of Tiptree’s closest friends. “Ursula, Ursula, I am petrified,” Alice wrote. “All the friends, the sf world—will they take it as ‘deception’? Will I have any friends left? Will the women who mean so much to me see it all as an evil put-on?”

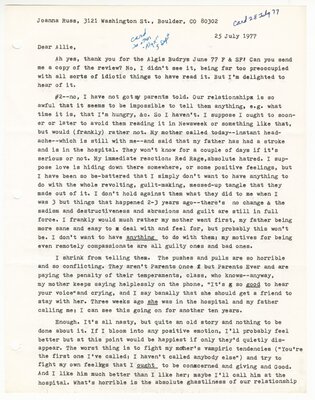

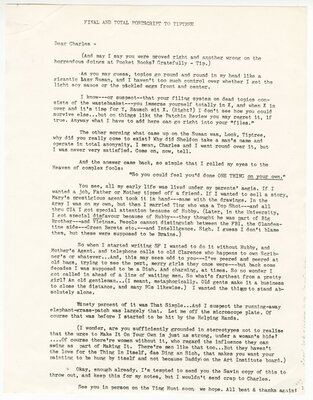

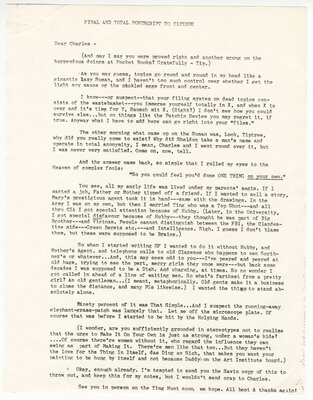

Le Guin and others assured Alice of their unwavering friendship, but the revelation that she was a woman changed how everyone read Tiptree’s work.

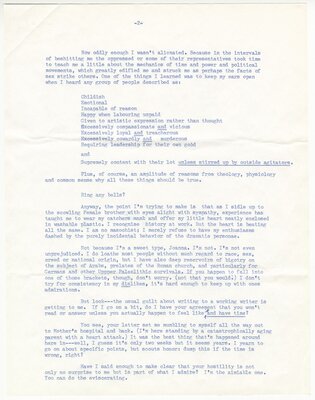

Her performance inflamed debates about gender already raging in literary circles. Was women’s writing fundamentally different from men’s? Some believed that it was inherently less potent. At the same time, feminist critics reread Tiptree’s stories in a new light: as texts about women that demonstrated there is a women’s way of writing—one that produces uniquely artful and incisive works all its own.

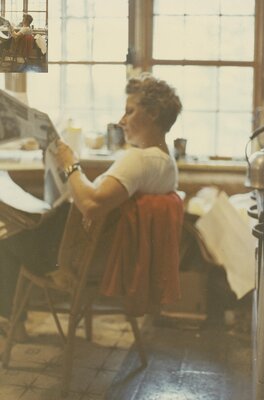

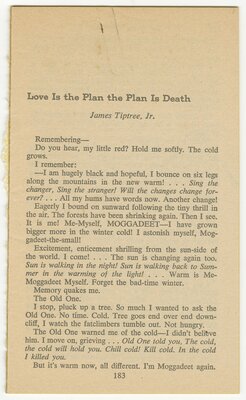

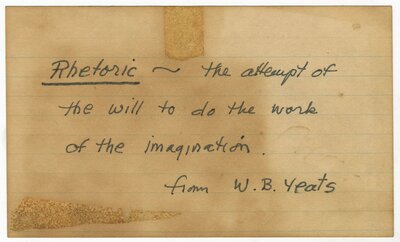

Ideally, Tiptree’s body of work may be read neither as male nor female, but as a rejection of gender identity. Alice Sheldon lived inside her body “as in an alien artifact.” Writing as Tiptree freed her. Like all cross-gender performance, it takes us past the perceived limitations of the self and opens up different possibilities. Not coincidentally, new vistas of possibility are also what science fiction promises.

Tiptree/Raccoona/Alice reminds us that gender is a social construct and, in the realm of literature, writers and readers both are complicit in its shaping.

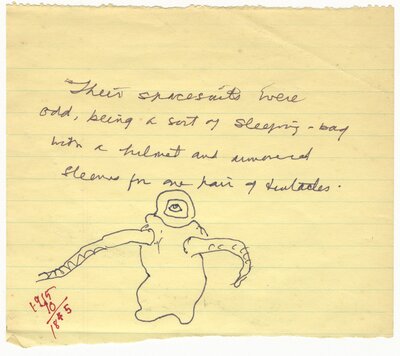

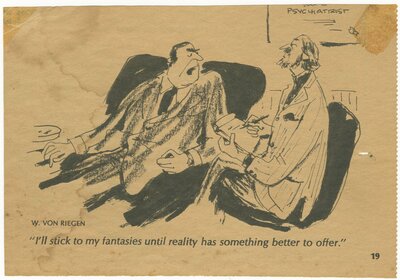

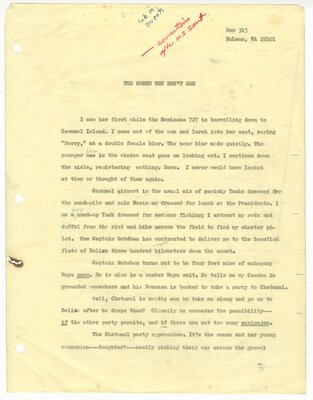

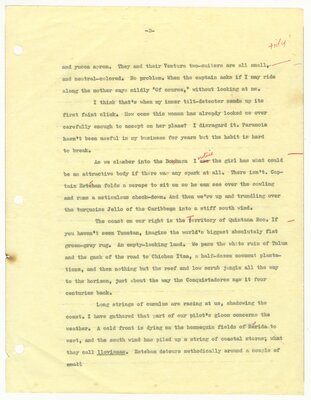

The complexities of gender and perspective are reflected in Tiptree’s comic-ironic and many-layered masterpiece, “The Women Men Don’t See” (1973). The story’s classic action-adventure plot is told from the first-person perspective of federal agent Don Fenton. When their chartered plane crashes in the wilderness, Don plays the protecting hero to a woman, Ruth, and her daughter. However, when a UFO arrives on the scene, Ruth tells Don she would rather go with the aliens than remain with him. The reversal forces readers to reconsider the many ways that the male narrator has misread the women throughout the story.

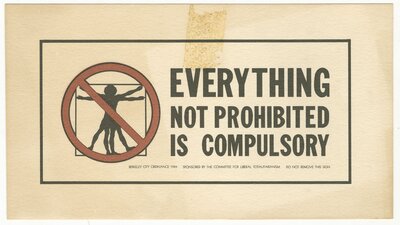

In a crucial scene, after Don asks Ruth about “women’s lib,” she replies that feminism has no chance: “Women have no rights, Don, except what men allow us. Men are more aggressive and powerful, and they run the world. When the next real crisis upsets them, our so-called rights will vanish . . . What women do is survive. We live by ones and twos in the chinks of your world-machine.”

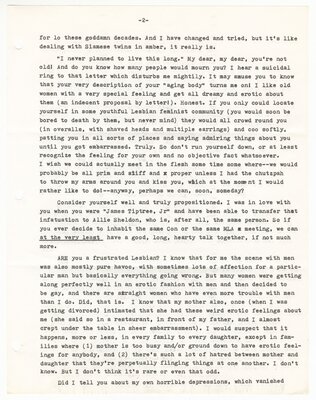

The two women leave with the alien exploring party, leaving Don behind to ask, “How could a woman choose to live among unknown monsters, to say good-bye to her home, her world?”

The story asks us, “Whose world?”

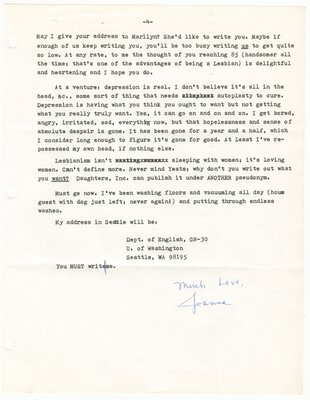

Alice struggled to recover from the death of her mother, the unmasking of Tiptree, and changes in her critical reception. She had difficulty regaining her writing identity and quit producing work for two years. In 1980, she started writing again under the Tiptree name, but the old authority and aggressive insistence of her earlier stories had gone. Alice wrote to fanzine editor Jeff Smith, “Do you know I miss Tip terribly—as a person? I bet you do too. ABS is a poor substitute.”

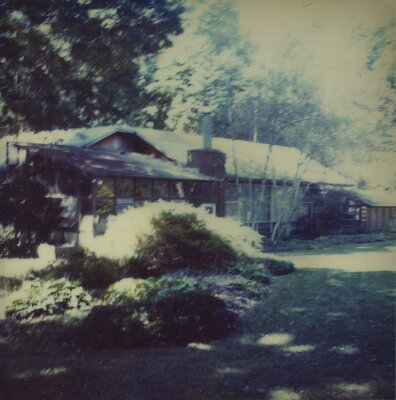

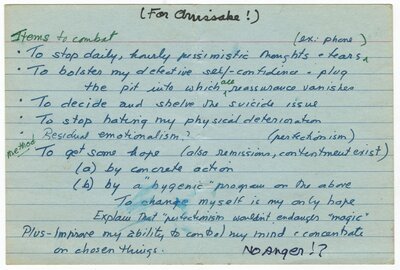

Many times in her life, Alice had dealt with deep depressions and thoughts of suicide. After her mother’s death at age 94, she talked with her husband, Huntington “Ting” Sheldon, about departing “while we were still us.” In the last years of her life, she confessed to friends that she often thought about exiting the world and her suffering for good. Ting loved and cared for Alice through these crises, but in 1986 his health deteriorated substantially.

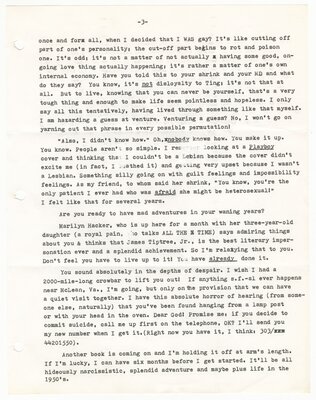

On May 19, 1987, when she was 71 and Ting 84, Alice fatally shot him and then took her own life.

Tragically, Alice B. Sheldon was unable to imagine a happy future for women, much less for herself. But in her life, she had exemplified the transformative power of imagination—and in her writing, she challenged us to question all of humanity’s future.

“Her brilliance and sweetness and quickness and courage burns like fire, it leaves a sense of suffering,” wrote Le Guin. “She lied to us yet she never betrayed us, never once.”