Hollywood Western

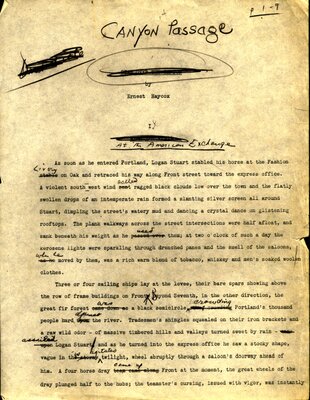

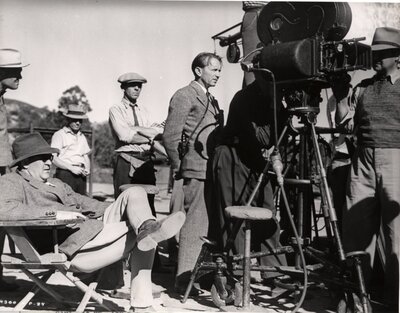

If the novels of Zane Grey provided the basis for the Hollywood Western in its early decades the innovative features of Haycox's fiction made his work particularly attractive to producers and directors attempting to extend the scope and range of the genre. Haycox's attention to historical and geographic detail contributed to a strong sense of cinematic location; his elaboration of secondary plot-lines gave screenwriters and directors ample material to develop his work for the medium of film; and his expansion of roles for women expanded in turn the possibilities for onscreen romance and conflict. While Haycox wrote only one screenplay, Montana, his novels and short stories were adapted for many significant films in the genre, including Union Pacific (1939, directed by Cecil B. DeMille, starring Barbara Stanwyck and Joel McCrea), Canyon Passage (1947, directed by Jacques Tourneur, starring Dana Andrews and Susan Hayward), and Man in the Saddle (1951, directed by Andre de Toth).

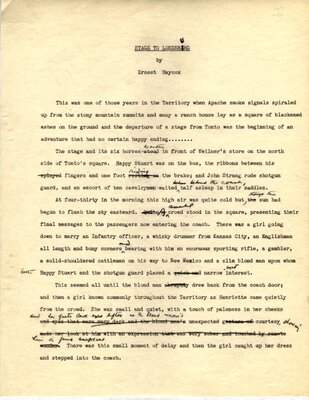

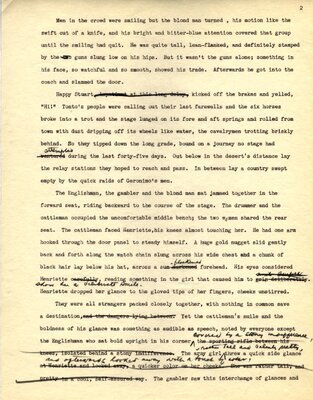

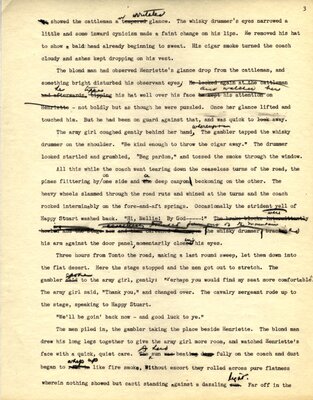

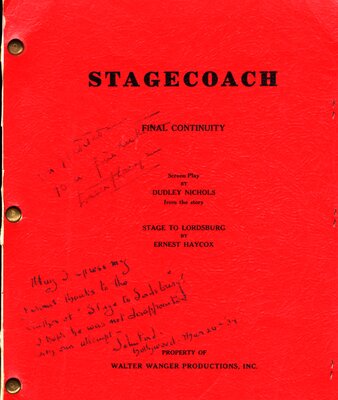

But even without his contribution to these and other Westerns, Haycox would certainly be remembered for writing one story that in its cinematic adaptation changed the very course of the genre: his "Stage to Lordsburg" (1937) served as the basis for Stagecoach, the John Ford film that both reestablished and redefined the Western. Beginning his career in 1917, Ford had directed a number of action Westerns which featured such important actors as Tom Mix, Hoot Gibson, and Harry Carey. These Westerns, and the scores of others produced during this period, were small budget, quickly produced "B-movies" designed for a largely male and rural audience. When Ford read Haycox's "Stage to Lordsburg" in Collier's Magazine, he saw in this story the elements for a new kind of Western, one which would elevate the genre and expand its audience. Stagecoach realized Ford's ambitions: if Haycox had taken Western fiction from the "pulps" to the "slicks," Ford similarly delivered the Western film from the "B's" to the "A's" and established it as a major cinematic form.

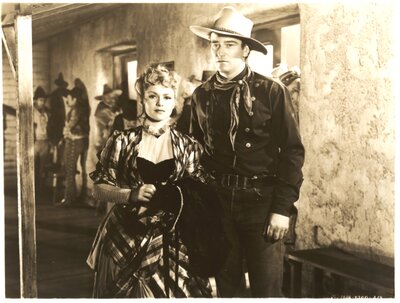

It is difficult to overstate the significance of Stagecoach: it managed to enshrine its director (Ford), its star (John Wayne, making one of film's most arresting entrances), and its terrain (Monument Valley, also making one of film's most arresting entrances) as icons in the cinematic representation of the West. But to say that Stagecoach is one of the genuinely great achievements of the genre is also to say that it embodies all the genre's contradictions: an acute sense of class coupled with a deep ignorance of race; an attempt to construct a democratic model of frontier community coupled with a violent exclusion of any element that might threaten community; an introduction of more complicated gender relations coupled with an entrenchment of traditional gender roles; a brilliant eye for landscape coupled with a real blindness to history. There are few subsequent Westerns that do not owe a considerable debt to this film, even if they set out to challenge its story or to counter its representations.