A Life in Labor

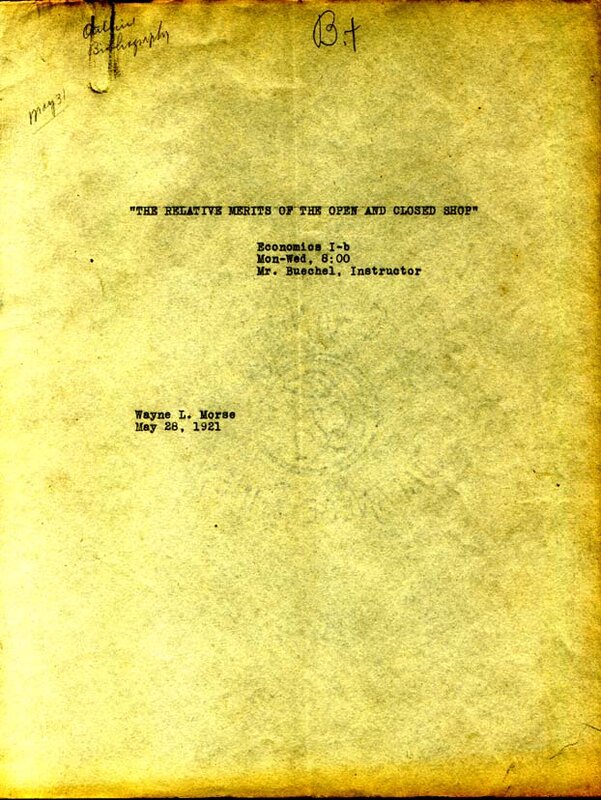

Towards the end of his sophomore year in 1921, Wayne Morse took a break in his busy college life to type out a paper for an economics class. The hurried appearance of the essay and the B+ grade reveal that Morse did not bring the full powers of his considerable intellect to bear on his subject, the relative merits of the open and closed shop systems of industrial labor. The ideas he set forth, however, were prescient. As he saw it, labor unions had every right to exist in America's work places, and the closed shop, which mandated that all workers at a job site be members of a union, was much preferable to open shop chaos. He fretted, however, about unions damaging the economy through arbitrary use of the strike and recommended that their ability to do so be severely curtailed. In place of the strike, he advocated a government-sponsored system of arbitration to settle industrial disputes. As he sat typing, Morse could not have imagined that the principles he set forth in this undergraduate essay would come to play a pivotal role in his own life and significantly impact the history of labor relations in the United States.

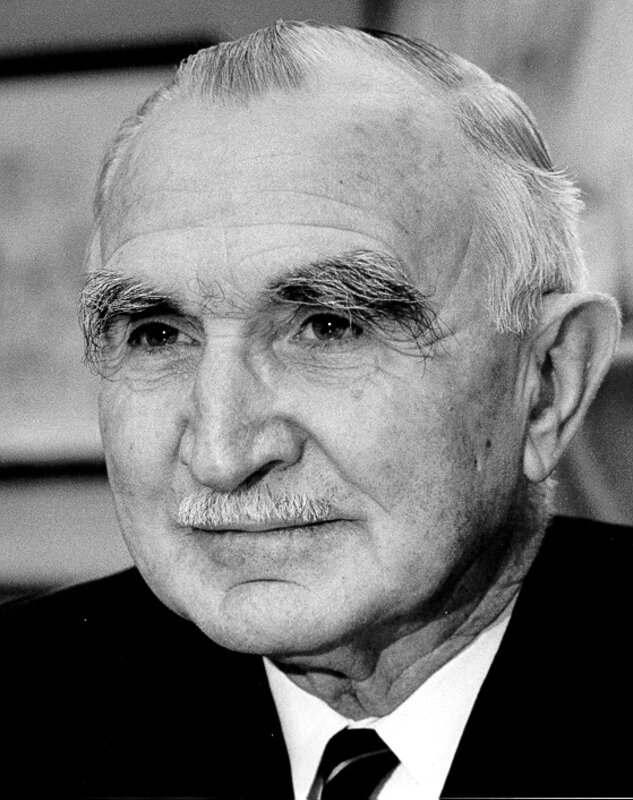

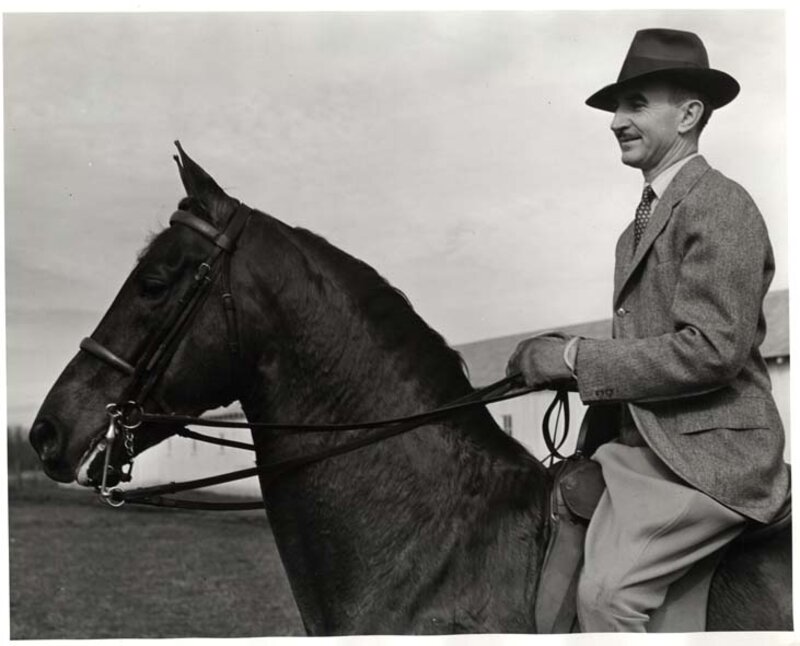

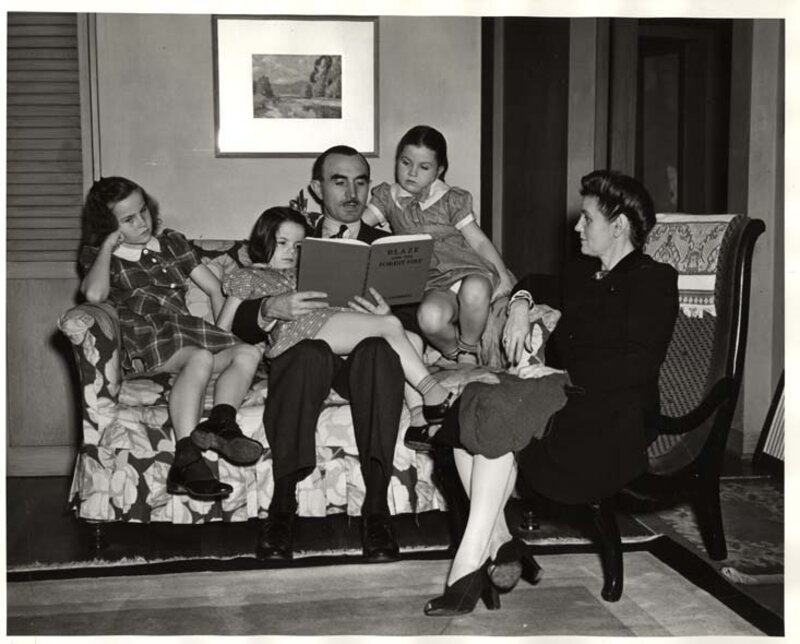

Born on October 20, 1900, Wayne Lyman Morse grew up in a rural Wisconsin farm family. His parents, Wilbur and Jessie, were life-long farmers, Baptists and progressive Republicans. They passed onto their youngest son a love of animals, an active moral sense, and the faculty to argue politics for hours on end. Although he would always find solace in the pleasures of farm life, especially in raising and riding prize horses, Morse bustled with an energy that demanded more than rural tranquility.

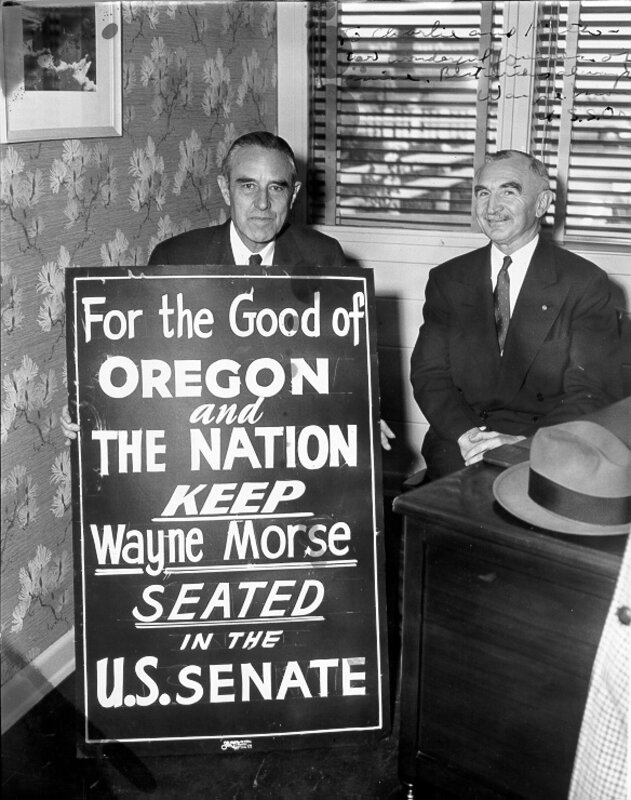

On the US Senate floor, battling with Democrats and Republicans both, Morse found a suitable outlet for his tremendous energies and demonstrated his superlative intellectual abilities. Representing his adopted state of Oregon from 1944 to 1968, Morse achieved widespread fame for his maverick nature and his fervent stance against the Vietnam War.

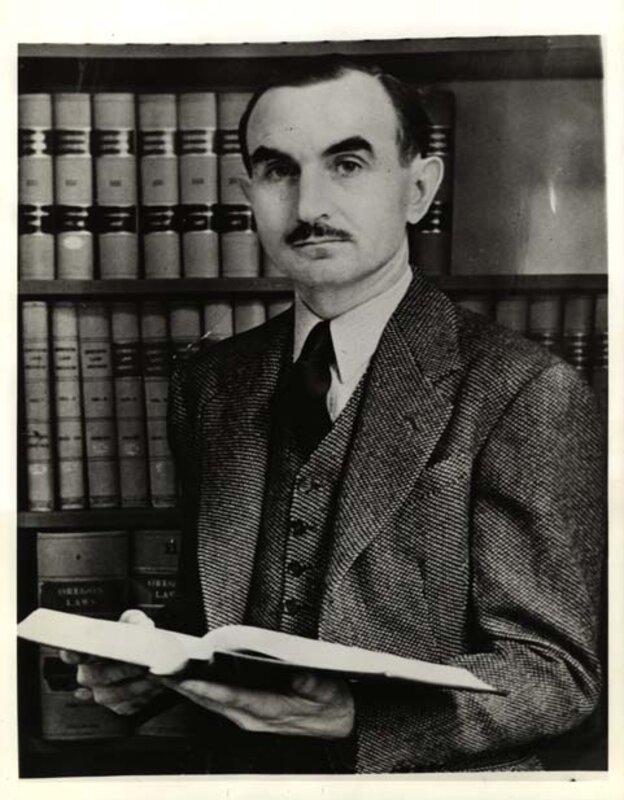

Before his days in the Senate, Morse had previously achieved a certain measure of renown when he became, at the age of thirty-one, the youngest law school dean in the nation. Although his post at the University of Oregon was not among the most prestigious, his swift rise brought him widespread notice.

Between these periods of limelight, Morse was one of the most respected labor arbitrators in the West and across the nation. In fact, in the late Depression his control over working conditions on the West Coast was so complete he was given the moniker, "boss of the waterfront."