Bringing Peace to the Pacific Shore

The years of the Great Depression were a time of upheaval for almost all Americans, and even for those lucky enough to find work, the twin specters of hunger and sudden unemployment haunted daily existence. To a certain extent, the working classes of the American West were able to rely on the natural resources that surrounded them to ameliorate these pressures, but they, like their urban counterparts in the East, also began to turn to unions to help ensure their right to a decent living while they labored.

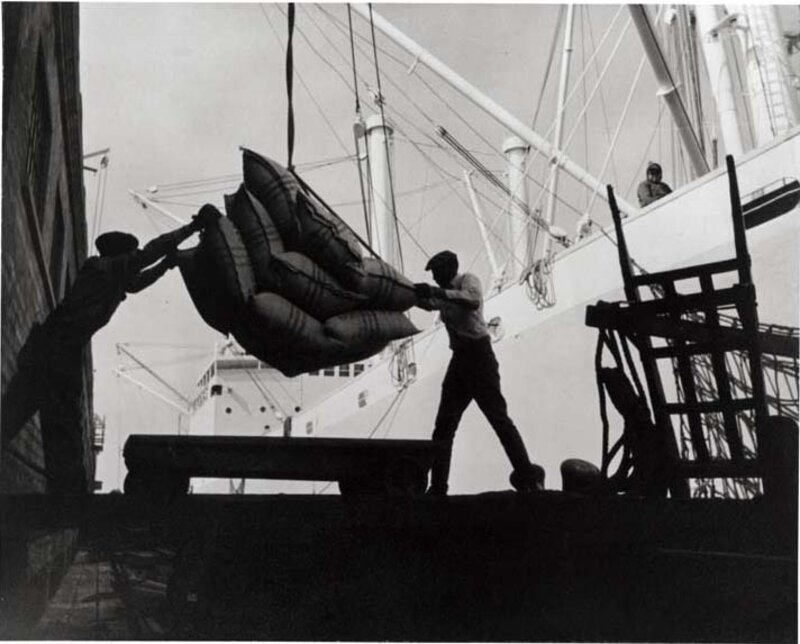

In 1934, the men who labored in the ports all along the West Coast united in an attempt to better their conditions and put an end to some of the more odious practices found on the docks. The longshoremen of San Francisco led an 81-day strike that became a successful general strike of San Francisco, but six workers were killed and many more injured in confrontations with police up and down the coast. Eventually, the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU) would emerge out of these conflicts with a good contract and a reputation as one of the most radical unions in the United States.

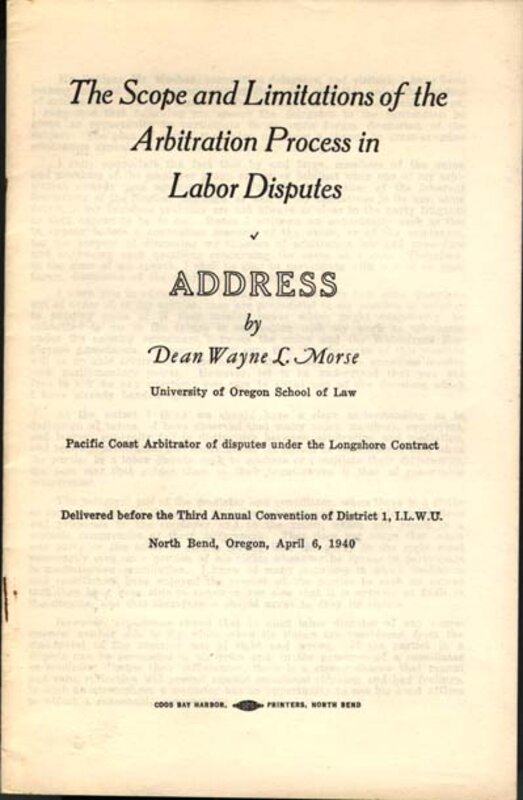

The men of the ILWU quickly discovered that securing a contract and enforcing a contract were two separate tasks. Over the next several years, both the ILWU and Waterfront Employer's Association (WEA) battled to interpret the provisions of the contract in ways most favorable to themselves. Because daily conflicts of this nature slowed the work and injured both groups, it became clear that they needed to find someone who could interpret the contract and arbitrate disputes in a manner that was deemed fair by both labor and management.

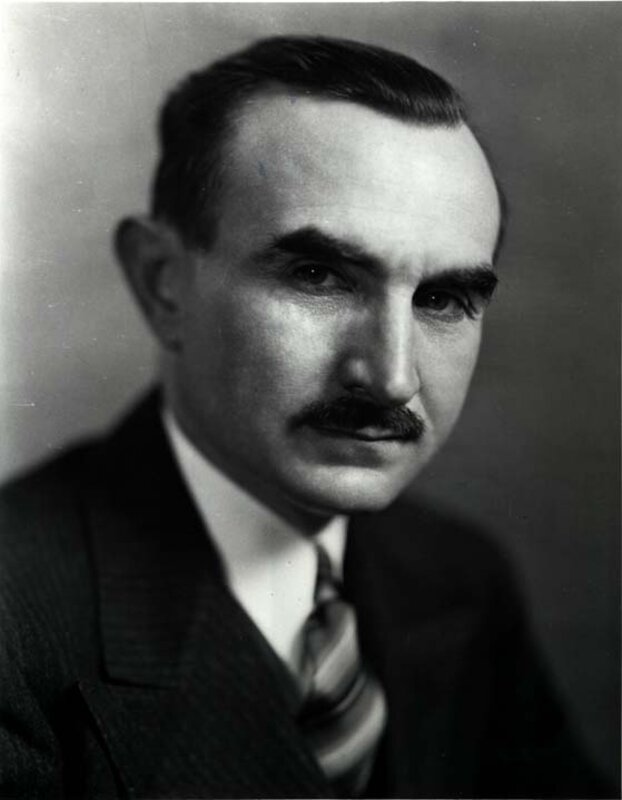

Back in Eugene, Dean Morse was growing restless behind his desk and began casting about for ways to use his surplus energies. After successfully arbitrating a couple of small labor disputes in Portland, he found the job to his liking and began to look for more of the work. Morse quickly gained a reputation for being fair and impartial, and his services were soon in demand all along the coast. So good was Morse at dissolving tensions and preventing long- term disputes or a repeat of the violence of '34 that in January 1939 the Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, appointed him Pacific Coast Arbitrator, overseeing the resolution of all conflicts between the ILWU and the WEA.

Morse was acceptable to both labor and management largely because he respected and upheld the fundamental tenants of both parties. In Morse the union found a man who respected their right to exist and defended their control of the hiring hall, ending the odious shape-up system and ensuring that only ILWU men could work the docks. The WEA liked Morse because he protected their right to set general work rules and to extract a profit from the work they oversaw. Moreover, he was extremely legalistic in his rulings. Morse believed it was his job to rule on the proper interpretation of the contract and this alone. He held himself aloof from politics and cronyism, and in this way he seemed to stand above the petty struggles to gain slight advantage.

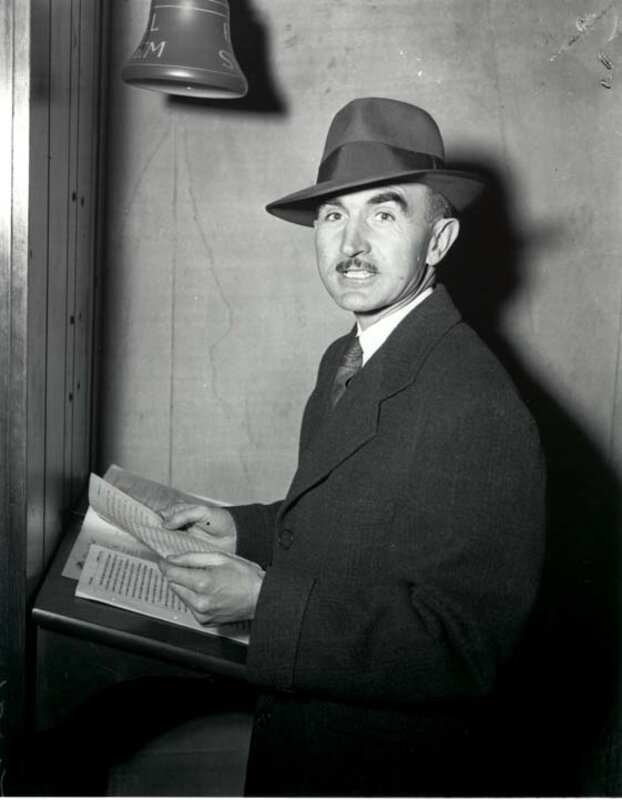

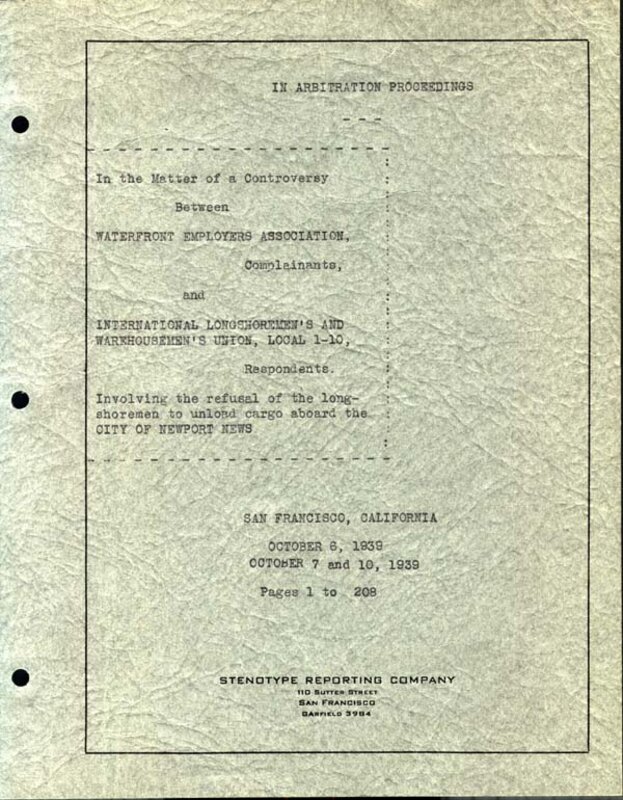

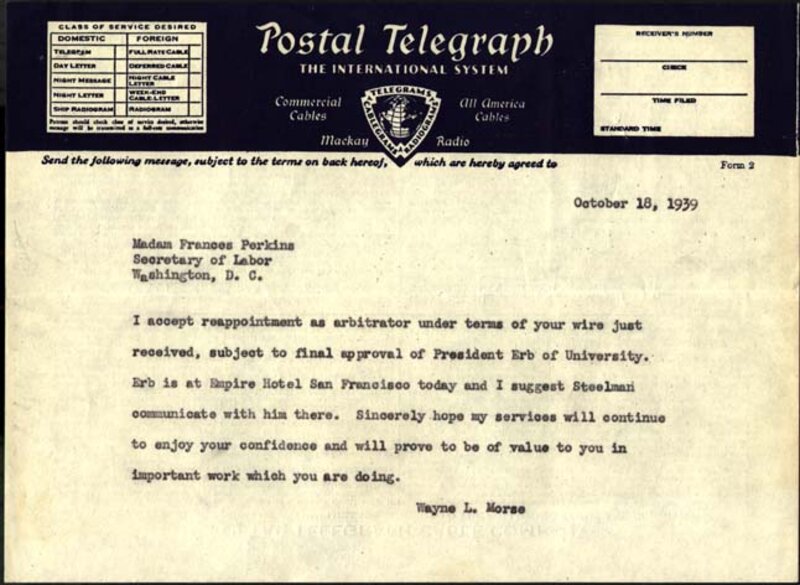

Although he was widely respected and recognized as a master arbitrator, things did not always go smoothly for Morse. In October 1939, the longshoremen in San Francisco refused to cross a picket line established by the fellow unionists the Ship Clerks. Morse rarely endorsed any strikes, and had long opposed this type of "sympathy strike." He ordered the longshoremen back to work, even if it meant crossing a picket line. Harry Bridges, the president of the ILWU, was naturally inclined toward respecting pickets and decided to test Morse's resolve, ordering his men not to cross. Morse reacted, ironically, by doing what he had so long opposed; he withdrew his labor. Catching a train back to Eugene, Morse refused to return to San Francisco until Bridges withdrew his order and Perkins formally requested that he return.