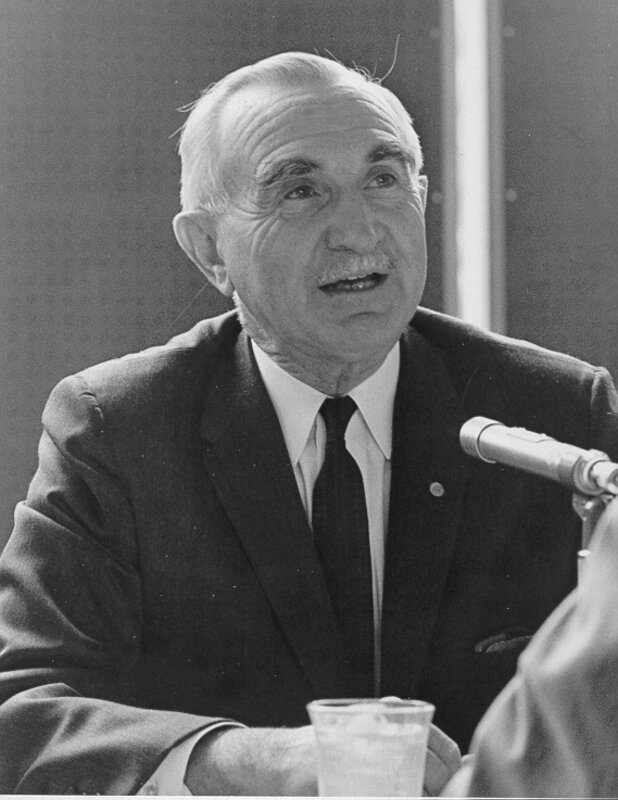

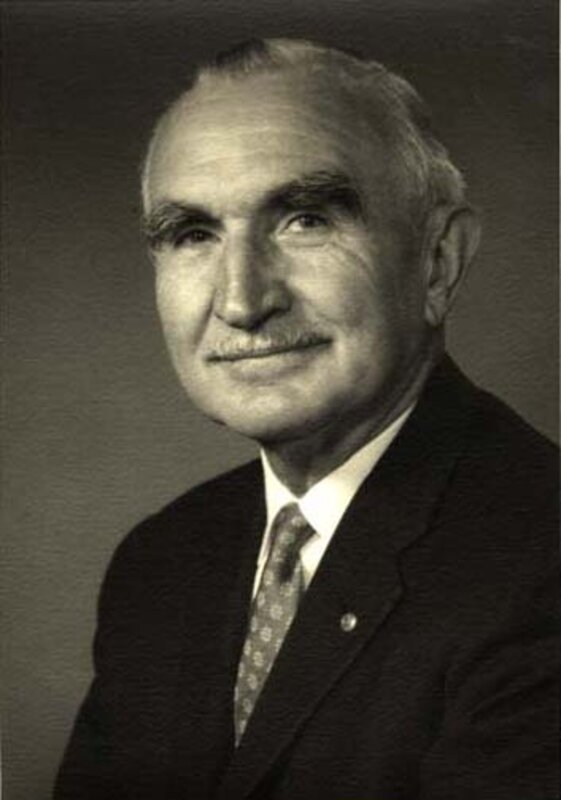

Battling for His Beliefs

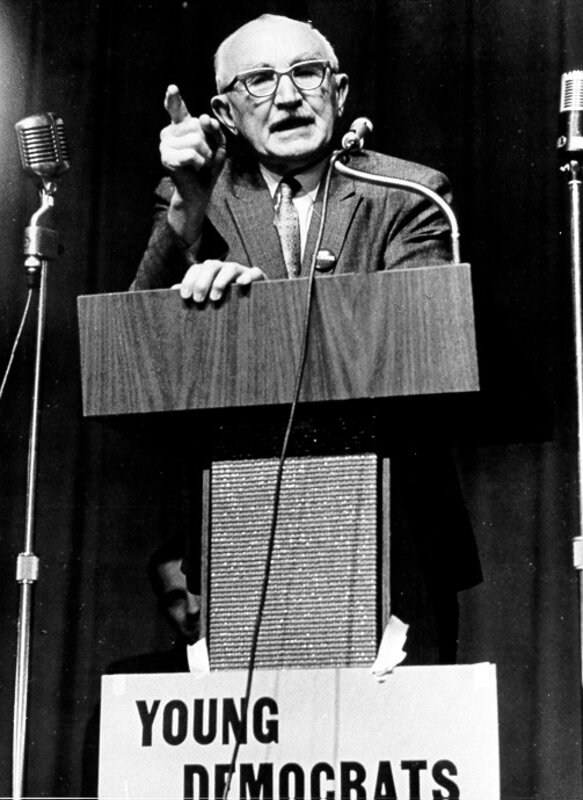

In 1945, after having finally left the deanship of the University of Oregon law school, Morse took his seat in the US Senate, a position he would not relinquish for another 24 years. Unlike the average freshman congressperson, who tends to stay quiet and learn the ropes before joining the fray, he wasted no time before pontificating on any issue that attracted his attention. Typically, he was arguing against the positions of his own party; he only voted with his fellow Republicans 30 percent of the time.

One issue that he clashed with his party over was the Republican-sponsored Taft-Hartley Act. Proposed in 1947, Taft-Hartley grew out of anti-union backlash that flowed from the tremendous increase in strikes following the war and the belief that many unions had strong ties to Communist Russia. The anti-union measure would restrict the ability to strike, allow states to require open-shop policies, and require union leaders to swear that they were not communists. Morse led a filibuster against the bill, in which he spoke for nine and a half hours uninterrupted, but to no avail; anti-union sentiment was too strong to be overcome by the efforts of the few liberals in the Senate.

By 1952 Morse strongly felt that the Republican Party was headed in the wrong direction, away from his liberal views to a more reactionary conservatism. He was disenchanted with the conservative rhetoric of Dwight Eisenhower, the Republican nominee for president, and was especially appalled by his choice for vice-president, Richard Nixon. Shortly before the election, he officially left the Republican Party and campaigned for the Democrat rival, Adlai Stevenson. For two years he was a one-man Independent Party, but in early 1955 he registered himself as a Democrat and he would finish out his career on the left side of the aisle.

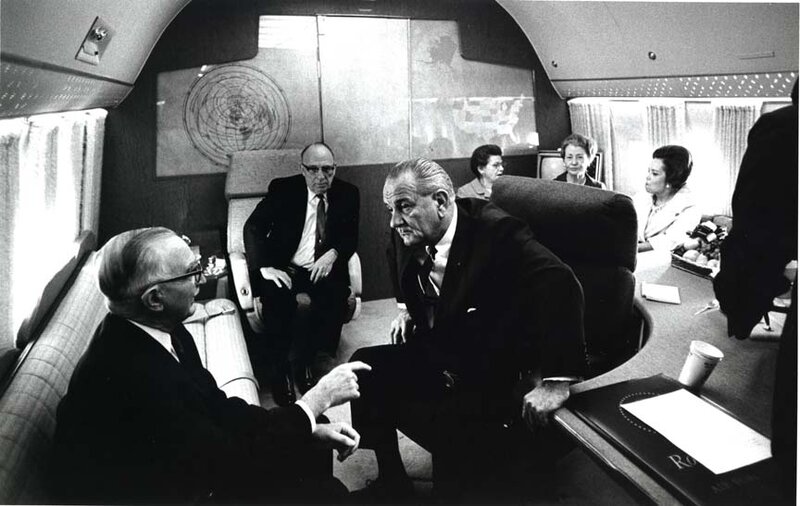

Through the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations Morse continued to be a thorn in the side of those who disagreed with him, especially his fellow Senator from Oregon, Dick Neuberger. However, it was in the Johnson years that his maverick behavior again came to the nation's attention.

On August 7, 1964 Morse stood with only one other congressional colleague to oppose the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. In response to an alleged attack on US ships patrolling the waters of North Vietnam, President Lyndon Johnson asked Congress to give him almost unlimited powers to persecute war against the communist nation. Morse feared giving the president such unlimited power, in addition to his belief that America had no purpose fighting in Indochina. Replying to constituent criticism of his stance he wrote,

It is one thing for politicians here at home, safe in the security of their political offices to vote to send young American draftees to die in an unconscionable war in Vietnam, but it is another thing to be one of those boys. I do not intend to put their blood on my hands.

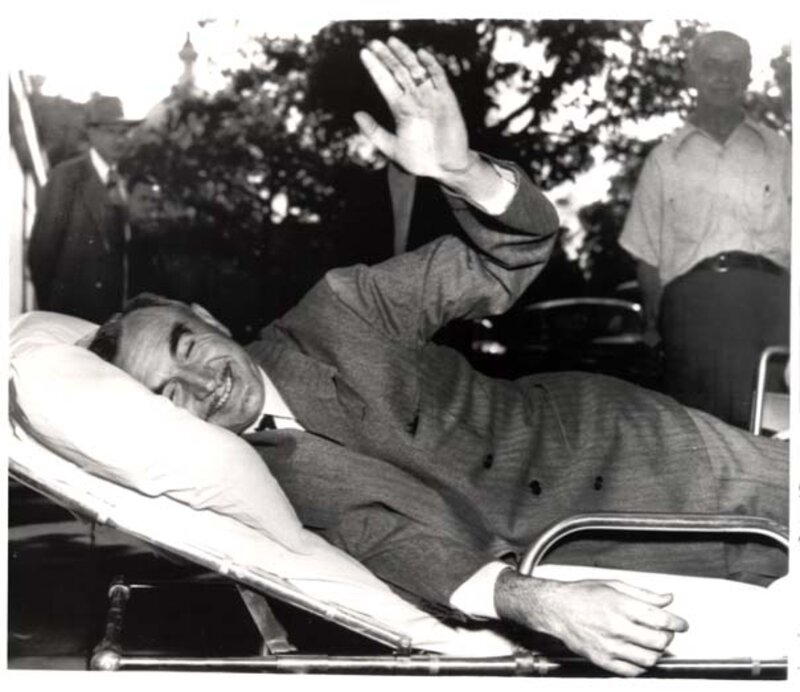

From 1964 until his death in 1974, he was one of the foremost opponents of the Vietnam War. Partially because of his Vietnam stance, partially because of poor campaigning, in 1968 Morse lost his Senate seat to upstart Republican Robert Packwood. Unable to fathom life far from the seat of action, he challenged Oregon's other Senator, Mark Hatfield in 1972. A convincing defeat in this election was not enough to dissuade him from running against Packwood again two years later. On the campaign trail in July Morse fell ill; three days later he died in a Portland hospital on July 22, 1974.