Coal, Conflict, and a Campaign

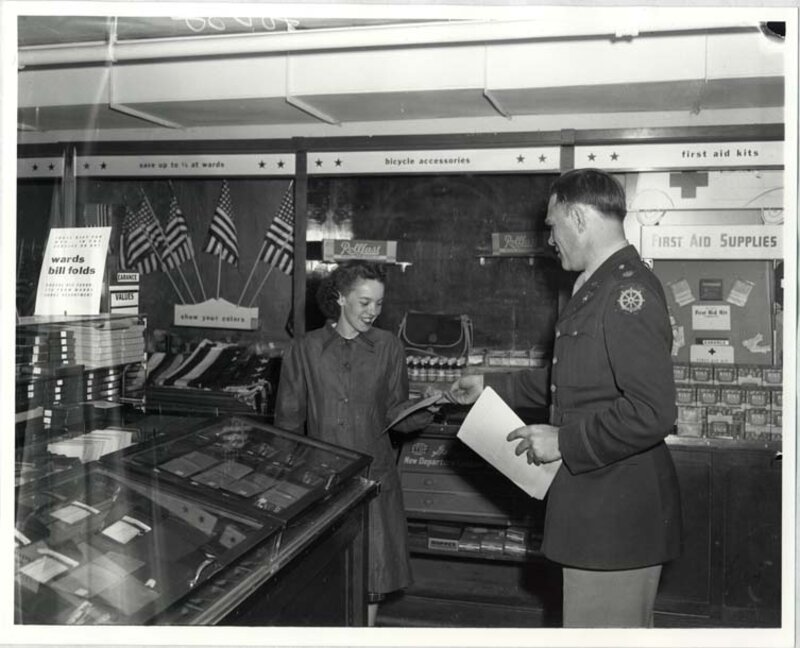

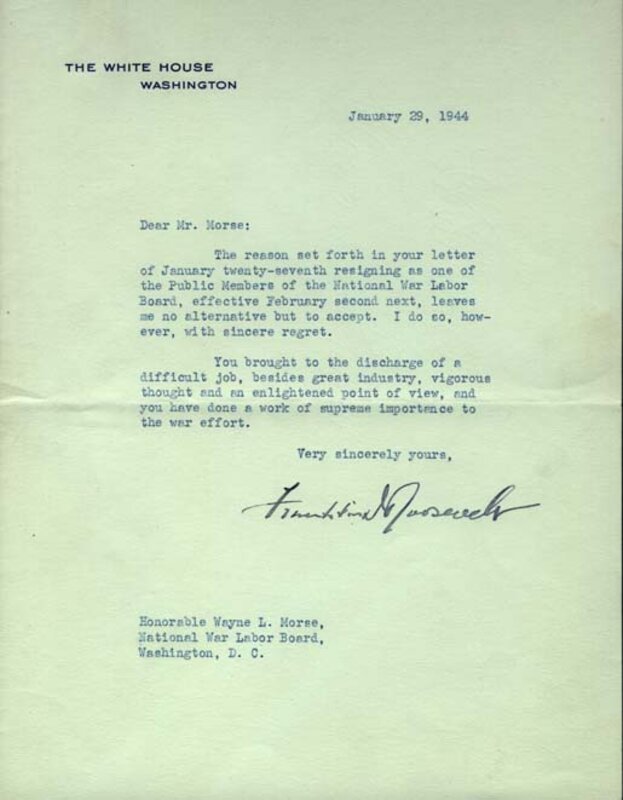

Morse spent three years working on the National War Labor Board, and for the most part he enjoyed professional success and positive public acclaim. Not all of Morse's dealings, however, turned out so encouragingly. In some cases his forceful personality and irresistible self-assurance proved to be a hindrance to the board and himself.

As it became clear that the Allies had turned the tide of the war, many unionists began to question the wisdom of the giving up their right to strike and turning their fate over to a government agency they could not easily influence. Although the leaderships of the AFL and CIO steadfastly stood by their No-Strike Pledge, the powerful president of the United Mine Workers, John L. Lewis, became increasingly vocal in his criticism of this policy. It was universally acknowledged that softcoal miners had the dirtiest and most dangerous jobs in America, and most everyone recognized that the miners were sorely under-compensated for their work. Deciding that the wartime emergency was the perfect opportunity to rectify this long-standing imbalance, Lewis led his miners out on strike.

Eleven members of the NWLB and many in the Roosevelt administration recognized that the miners had legitimate grievances and they argued that it was appropriate for the board to bend the Little Steel Formula enough to meet the demands of the miners. Morse, however, would do no such bending. Once a policy such as Little Steel was set, it was extremely difficult for Morse to see any wisdom in violating it. Moreover, as a man who had a dim view of strikes as an economic weapon, he was especially displeased when that weapon was used in an attempt to force him to violate his own principles. In this case, however, Morse was overwhelmingly outvoted, and he was unable, despite some vitriolic efforts, to bring anyone to his point of view.

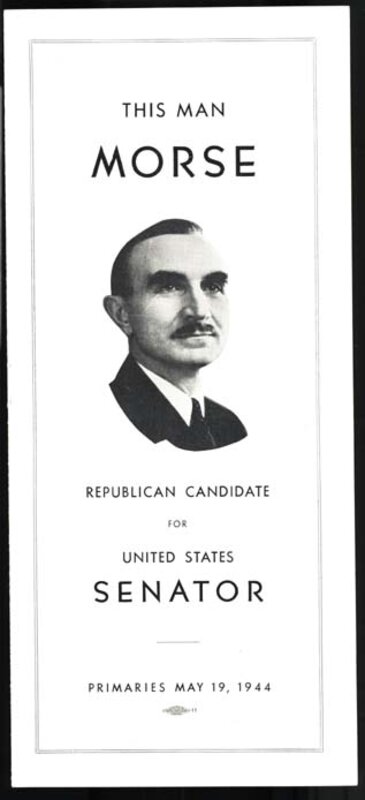

As the war ground on and the work of the NWLB became more monotonous, Morse began to turn his attention to arenas that could better absorb his energies and give him more satisfaction. His work at the law school could not fulfill these demands, but in Oregon there was a solution. Although Oregon had gone for Roosevelt in the Depression years, it was still considered a rock-solid Republican state. Despite their characteristic conservatism, in 1944 Oregonians had grown tired of their right-wing Senator, Rufus Holman, and Morse challenged him in the Republican primary.

Although he was running as a liberal Republican and he counted on Democrats for much of his support, to appease conservatives Morse was forced to distance himself from the Roosevelt administration and his sympathies for organized labor. Throughout the campaign his rhetorical skills packed halls where audiences heard him criticize the New Deal for being anti-free enterprise and “totalitarian.” Balancing liberal views and conservative rhetoric, Morse edged out Holman in the primary and went on to crush his Democratic opponent in the general election.