An Audience with an Emperor

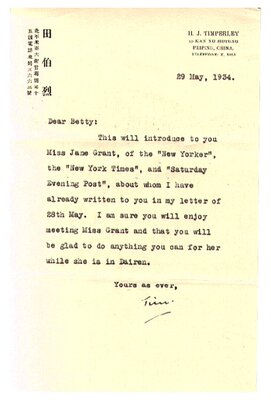

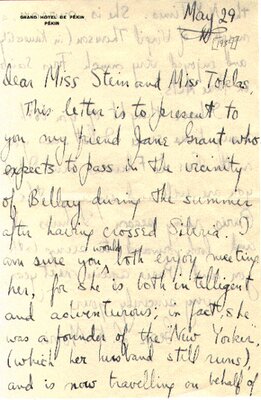

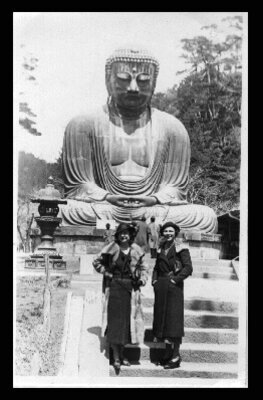

What inspired Jane Grant to leave New York in the spring of 1934 to embark on a seven-month journey through China, Japan, Russia and Europe is not entirely clear. One imagines that her reasons had much to do with the art of adventure itself. When she arrived in Manchukuo (Japanese-occupied Manchuria) Grant accepted the dubious honor of being the first woman and first reporter to be granted an audience with Pu-Yi, the puppet Emperor, a man she described as having highly expressive fingers. From Manchukuo she traveled solo by train and then joined the Trans-Siberian express finally arriving in Berlin just in time for Hitler's initial takeover of Germany. "My letters of introduction turned out to be for the wrong people, for with one exception they had all disappeared," Grant later recalled.

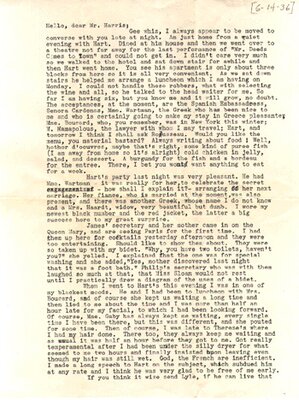

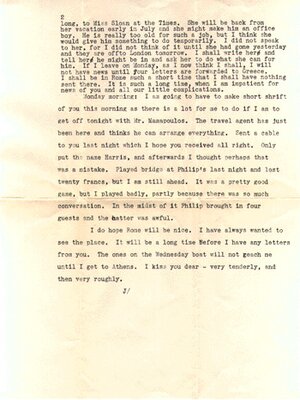

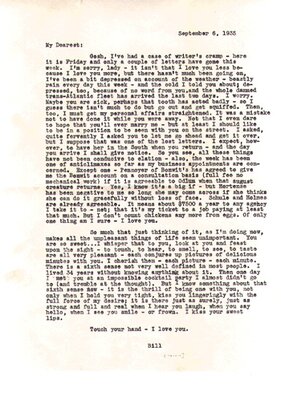

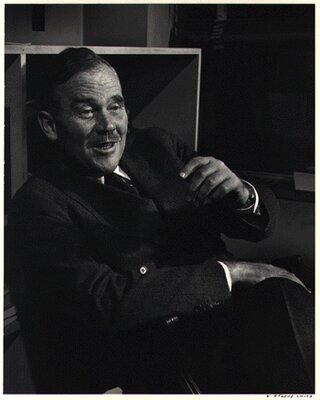

Sometime upon her return to New York, Jane Grant was introduced to William Harris, a financial analyst and later, an editor at Fortunemagazine. They soon began a heated affair, which was cut short by Grant when she suddenly decided to return to Europe. Harris was left to declare his pent-up passion for her with typewriter ribbon and paper. At one point, Grant teases him about the obvious pleasure he takes in writing her these love letters, "You won't need me anymore," she chides. At the time, in the summer of 1935, Harris was still entangled in a failing marriage and Grant's trips abroad may well have been her way of keeping a well-considered distance from this charming, but married, man.

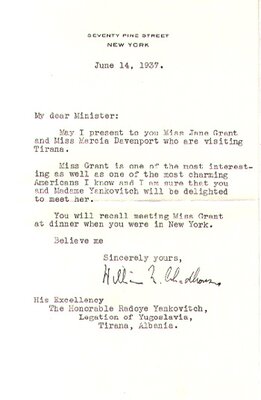

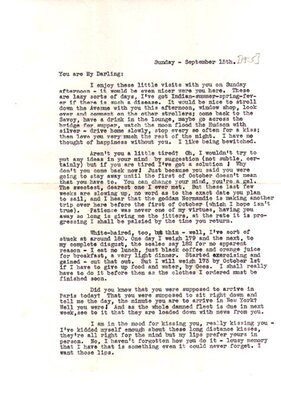

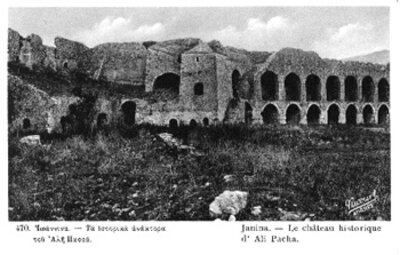

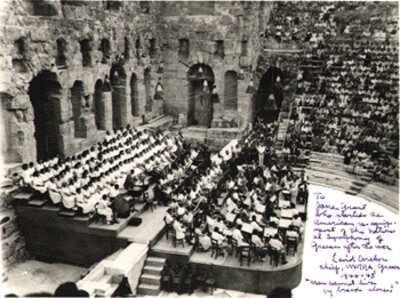

For the next two summers, Grant returned to Europe. Her position as New York Times general reporter allowed her the freedom to travel and file her stories via telegraph. Some of her destinations were quite remote: Budapest, Tirana, and Dubrovnik were all listed on Grant's travel itinerary. And everywhere she stayed, she seemed to dine with foreign dignitaries, attend the symphony, and inevitably go out dancing. Driving across Eastern Europe with her friend Marcia Davenport during the summer of 1937, Grant managed to find time to write to Harris almost daily. Her letters are filled with a range of adventures from changing flat tires in Hungary to meeting the Windsors in a shoe shop in Italy.

Grant's letters depict a woman who is direct in affairs of the heart. "I kiss you dear--very tenderly and then very roughly." She suggests to Harris that he see his other girlfriends while she is away so that she may have him all to herself when she returns. In another letter, she suggests that he sort out his business with his first wife, "If you are a married man when I come back I don't want to see you." And later, she questions whether she still loves him at all when she is travelling on one side of the Atlantic and he is faraway on the other.

"No, I don't love you very much right now, for I don't think you are listening and words of love are precious and I am certainly not going to waste them. Of course I might be persuaded to like you but that sort of thing has to come with time. Couldn't you learn to like me? Or would you rather go to hell?"

Grant and Harris married in 1939 and seem to have enjoyed a loving and playful thirty-three years of marriage together. In 1950, they founded White Flower Farm, a highly eccentric and successful nursery just outside Litchfield, Connecticut situated on the premises of the couple's summer home--an abandoned barn that they remodeled into a three-story house. In a love letter from this later period, Grant's epistolary style, still as spirited as ever, albeit more succinct, reads, "Dear Sir, This is to notify you that I love you madly." And by all accounts, she did.