Ready to Combat the World

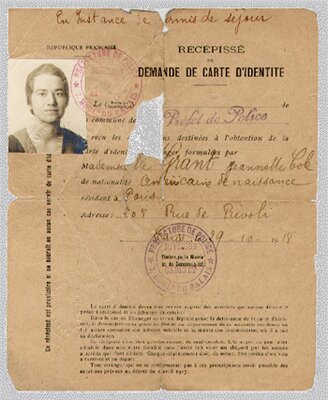

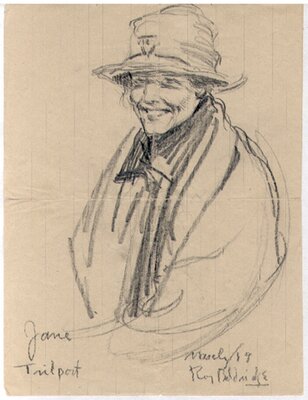

Jeannette Cole Grant born May 29, 1892 in Joplin, Missouri was a woman several steps ahead of her time. Feminist, journalist, gardener, and entrepreneur, Grant moved among these identities with a studied practice of power and grace. Jane Grant, as she was known throughout her life, was a survivor who played by her own rules. With little status or economic privilege, she made her way in the world using brains, bravado, and anything else that came her way. In the mythic tradition of the American rags to riches story, it is expected for the farmer's son to leave home to seek his fortune, yet it is quite rare for the farmer's daughter to escape--especially without a husband or doting aunt in tow.

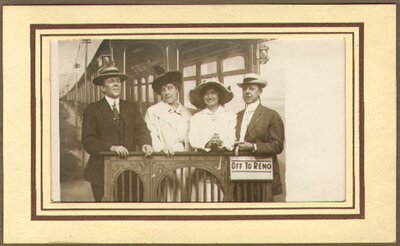

In 1908, one week after high school graduation, Grant pointed her compass north towards New York City. She was thrilled to be boarding the train with Miss Willie Warner, the former Girard High School music teacher who had married and moved east. Warner offered Grant the opportunity to live with her and receive voice training in New York. At sixteen years old, Grant had never been further from her father's farm than Kansas City. However, she jumped at the chance to leave home; she was, in her words, "ready to combat the world."

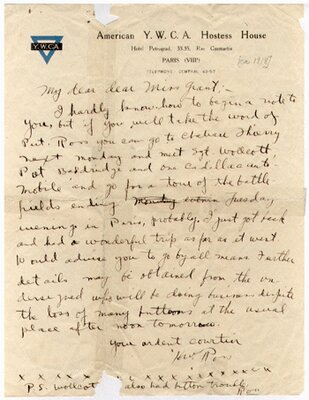

Towards the end of Grant's first year in New York, Miss Willie Warner died and in spite of the loss of her friend, Grant decided not to return to her father's farm in Kansas. At this point, Grant was desperate for work and sang anywhere she could get a booking--clubs, "smokers," cheap restaurants, and the Church of St. Mary the Virgin. But there was never enough money to pay the rent and buy food. Eventually, with the help of her landlady, Grant found a steady job answering phones for $10 a week at The New York Times.

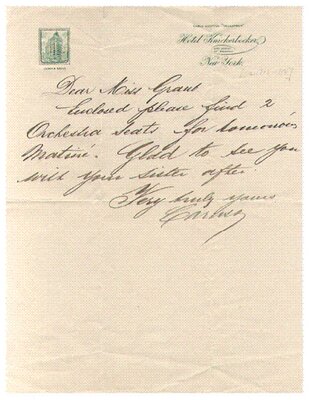

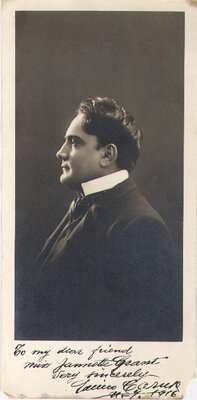

"Fluff," as she was known to everyone at the Times,answered phones for a very long time. And although she had been told that "there would be no advancement, that women were merely tolerated at the Times,"Grant insisted on spending her free time drafting news articles, stories culled from her daily experiences. Eventually, her boss realized he could profit by Grant's zealousness and began training her to cover stories. Grant reported on stag parties, weddings, and the evening activities of the rich and famous. Writing for the society pages is how Grant came to meet the Italian singer, Enrico Caruso, one night at the Hotel Knickerbocker.

Caruso was in New York to listen to his favorite divas sing, and, on occasion, invited Grant to accompany him to the opera. When he left town he gave her a gold bracelet, his profile embossed on a single, dangling charm.

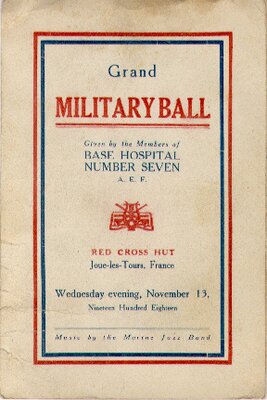

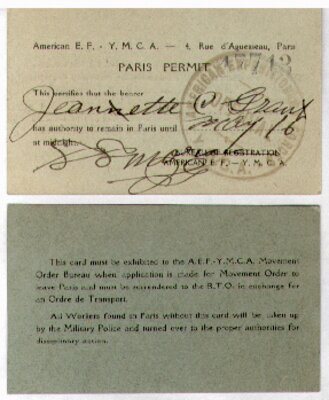

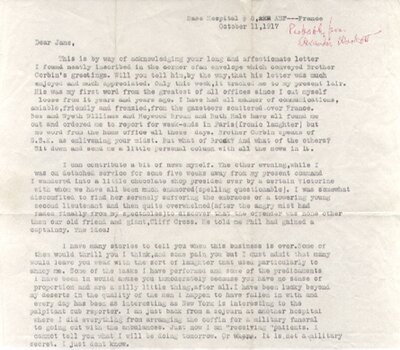

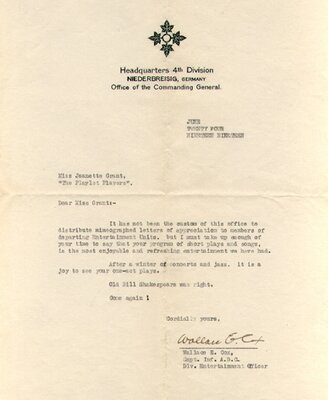

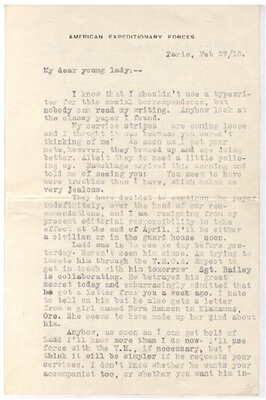

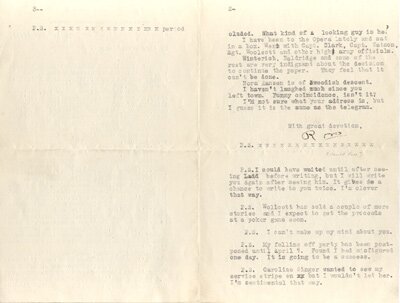

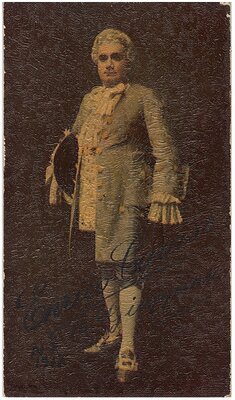

At the Times,Fluff gave fox-trot lessons in the halls and in turn, the men taught her "red dog and poker." When her good friend and fellow reporter, Alexander Woollcott, went off to fight in World War I, she decided she would go too. Her prodigious letter writing coupled with Woollcott's assistance led her to a job with the YMCA Entertainment Bureau performing with "The YMCA Playlets" in Bordeaux, Le Mans, and Paris. "With them I did some of the hammiest playlets ever put on paper," Grant later wrote. She also recalled the time in Paris as one of the most thrilling experiences of her life.

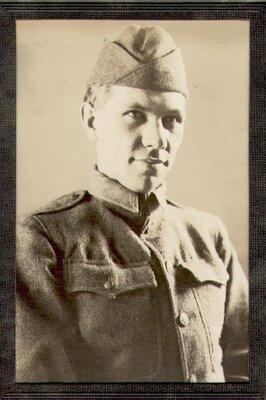

It was while in Paris that Grant met Private Harold Ross at a poker game near Montmartre. He crossed the room to kiss her hand and was, immediately, smitten. He was impressed with her double profession of reporter and entertainer. A woman with brains and beauty. For her part, Grant remembers a man that resembled nothing more than "a misshapen question mark." Yet, as Ross started to court her with trips to the opera (which he hated), elaborate corsages (which the YMCA dress code forbade) and bottles of perfume, his homely features and unique hairstyle slowly endeared him to her.

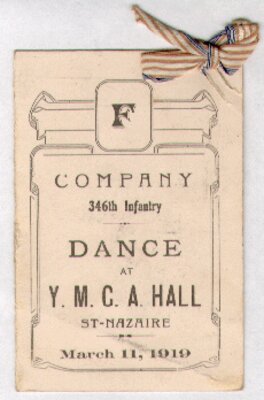

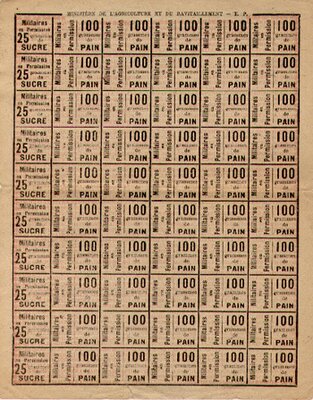

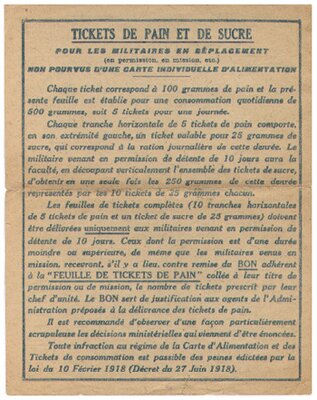

After she said good-bye to Ross in Paris in the spring of 1919, at a time when bread and sugar were still rationed, Grant set off on tour with the YMCA to visit the allied forces. The theater group performed at Versailles, Fontainbleu, and on sailing boats along the Seine. Picnics along the Rhine, dinner in Belgium, beer from Holland--all of this was lavished on these young, available American women.

"At dances where doughboy bands furnished the music, generals would lure us to balconies to hear the nightingales--and there they would make passes at us. My conscience was now somewhat dulled... I suppose I took on the coloration of the generals, for I too, was in a mood for comfort, sightseeing, and any fun that might come my way."

Many years after her days as an entertainer of Generals, Grant sent to Raoul Fleischmann, the publisher of The New Yorker, the following story: a maiden aunt, who, upon seeing an over-sized bottle of perfume on her post-debutante niece's dressing table, admonishes her, "my dear, no nice girl would have such a large bottle of perfume." And the girl's retort, in a voice very much like Grant's own replies, "but Aunt, no nice girl would get such a large bottle of perfume." What made Grant both a party girl and a feminist, a club entertainer and a co-founder of the Lucy Stone League is not too difficult to surmise. Grant believed in living life as she pleased, and that included never allowing seemingly paradoxical situations to stand in her way.