The Legacy She Left Behind

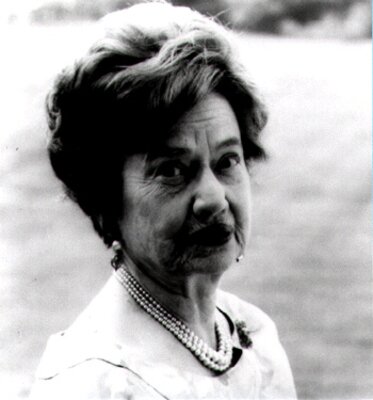

Jane Grant was a "networker extraordinaire" before the term was ever embraced by popular culture. She charmed military officials, high society, and gardeners with grace and finesse. And perhaps most importantly, Grant had the tenacity needed to see a project through--be it a memoir, a magazine, or the dream of a white flower farm.

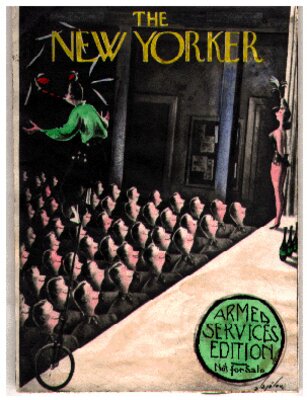

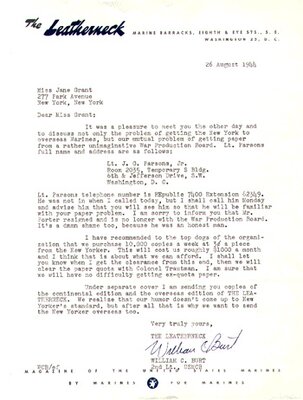

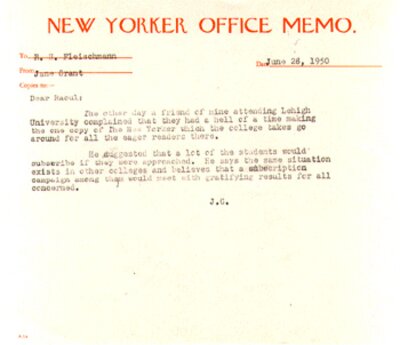

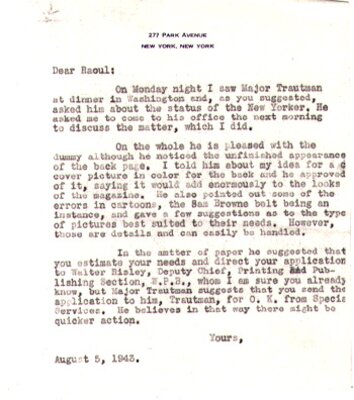

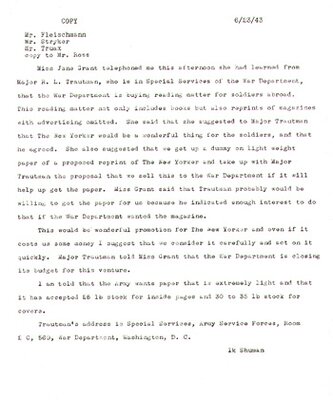

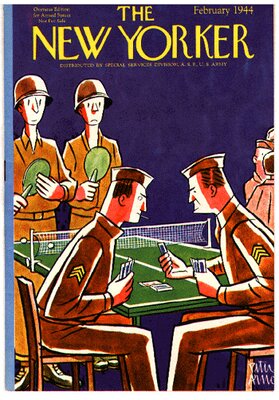

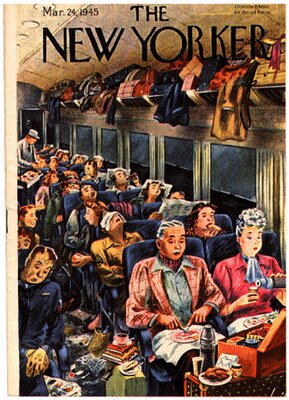

Grant's initial work with The New Yorker in the 1920s had involved shaping the circulation department, and she maintained a keen interest in seeing subscriptions grow. In the early spring of 1943, Grant proposed and subsequently fought for, a "pony" or downsized edition of the magazine. The "little New Yorker,"as Grant called it, would be bought by the government and supplied to the armed forces overseas. It would rely on a heavy dose of cartoons, humor, and war related features to entertain the troops. "The New Yorker generally keeps its fun clean, and is, therefore, an important addition to the [soldiers'] morale..." Grant wrote. Unfortunately, neither Raoul Fleischmann nor Harold Ross showed interest in the project.

It was not a surprise that Fleischmann tried to stonewall the idea. One year earlier, Grant had organized disgruntled stockholders against the publisher demanding an investigation into his management practices. The stockholders, headed by Grant, threatened to sue unless Fleischmann relinquished his position as board chair. After protracted negotiations, he did retain his title, although his power was greatly diminished. Not coincidentally, this marks the start of Grant's intensified involvement with the magazine.

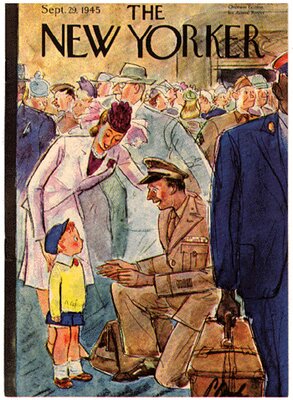

Despite Ross and Fleischmann's strong misgivings, the little New Yorker proved a success in every conceivable way. Grant made influential friends within the military, sending copies of the magazine to General MacArthur and other officers of note. The public relations maneuver paid off. The New Yorker'scirculation nearly doubled, feathering out to all corners of the country in the two years after the war. Officers and servicemen who read the little New Yorker overseas were now anxious to subscribe and it didn't matter whether they had returned to Boise or Boston.

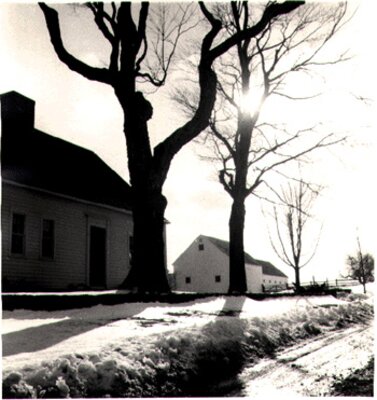

Ironically, by 1947, Grant herself was no longer a full time New Yorker. She and William Harris, her second husband, were spending increasing amounts of time at their country home in Litchfield, Connecticut. The project began as a straightforward renovation--the couple bought an old barn and converted it into their private getaway. But as neighboring farmers began to retire and sell off their land, they offered Grant and Harris the right of first refusal. "There's nothing like owning a house and one acre and protecting it with 90 acres, a horse barn and a dog kennel. What are we going to do with them?" Grant asked Harris.

By this point the couple had become rather dedicated gardeners. The border around their house boasted an all white planting of perennials and flowering shrubs--what English horticulturists call a moon garden. And from this flowering border came the idea of White Flower Farm. The commercial feasibility of selling only white flowers was soon discarded, but the engaging name remained. Begun in 1950, White Flower Farm is still perhaps the most highly respected and innovative nursery in the country. This successful company brings to three the number of organizations that Grant co-founded, all of which remain vibrant and dynamic institutions today, long after her death.

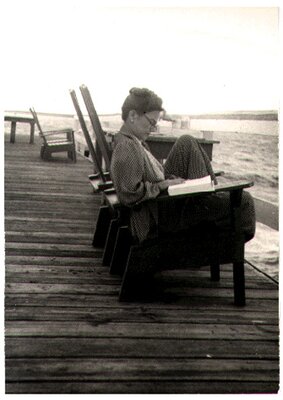

It was during her years at White Flower Farm that Grant began composing her memoirs concentrating on her early life with Ross and the magazine they founded. Ross, The New Yorker, and Me,published in 1968, chronicles the story of New York in the 1920s and the frenetic lives of the Algonquin Round Table crowd; but it also provides insight into the woman who, born in a small Missouri town, managed to work her way to into New York society without pedigree or independent means.

"For a long time now I have been regarded as a substantial individual, quite competent to administer my own affairs. True, I am married to Mr. William Harris, but at no time do I use his name. I have never yet felt the need for an alias. The enclosed brochures may enlighten you on the subject of one's name... It might be a good idea to file them in your library."

Grant was seventy-seven when she reprimanded Dr. Howard Gottlieb of the Boston University Libraries for addressing his letter to "Mrs. Harris." Gottlieb quickly responded apologizing for his unintelligent behavior and offering Grant his sincerest admiration. She, in turn, thanked him and, harboring no ill feelings, worked to enlist him as a supporter for the Lucy Stone League.

Grant died at her home at White Flower Farm three years later on March 16, 1972. She was eighty years old. Jane Grant, who by her own force of character made her way in the world left an important legacy behind, the legacy of a woman who lived by her own rules. And won.