Life as a Lucy Stoner

The Lucy Stone League, founded in 1921 by Jane Grant and her friend Ruth Hale, was simple in its stated aim of encouraging women to keep their own names, yet sophisticated in its public relations and political reach. The event foreshadowing the organization's inception occurred on February 18, 1921 when Ruth Hale, a well-known theatrical agent, returned a passport to the U.S. State Department which had been made out to "Mrs. Broun." Hale declared she would not go to Europe under such circumstances. "I threw the government overboard, and refused flatly to go abroad," she told a New York Telegraphreporter. A few weeks later Grant and Hale called a meeting of women who "believe in the right of women to keep their own names." The Lucy Stone League was born, with actresses, journalists, and public relations professionals in attendance. Hale was elected President and Grant chosen as Secretary-Treasurer.

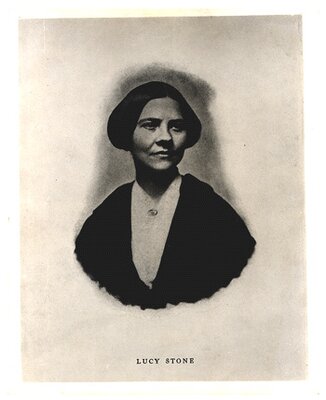

The Lucy Stone League chose its name to honor Lucy Stone (1818-1893), a Massachusetts born woman who advocated for suffrage, civil rights and the abolition of slavery. Upon her marriage in 1855 to Henry Blackwell, a hardware store proprietor, Stone kept her own name rather than taking his--an unheard of aberration at the time. But Lucy Stone knew her rights. Instead of stopping at this radical yet single gesture, Stone and her sister-in-law Elizabeth Blackwell, the first American woman ever to receive a medical degree, set out to change the status of women via the U.S. court system. They challenged state and federal laws that allowed a woman to be seen as a commodity belonging to her husband, laws that allowed her to be beaten and denied her property or inheritance.

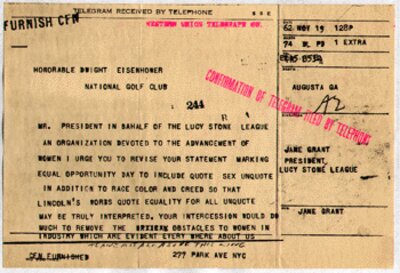

Immediately upon its inception, the League embarked upon a variety of projects all designed to promote the rights of women. This meant the right to hold her own property, to believe in her own ideas, to be full partners with men in society. During the early years, the League focused explicitly on a woman's legal right to keep her own surname after marriage and be recognized by that name. This meant communicating with high officials at the Library of Congress, the U.S. Passport Agency and the U.S. Marines asking them to re-structure their catalogues, application processes and entire traditions.

Interestingly, Grant credits Harold Ross, her first husband, with bringing up the issue of her name moments after their marriage ceremony, "Jesus Christ, I don't think I like that Mrs. Ross stuff," said Ross as they walked through the churchyard to the street. "Maybe Ruth Hale's got something after all." However, this initial support for Grant to hold onto what was hers soon disappeared. After their divorce, Ross wrote to a friend, "I never had one damned meal at home at which the discussion wasn't of women's rights... she and Ruth Hale had maiden name phobias."

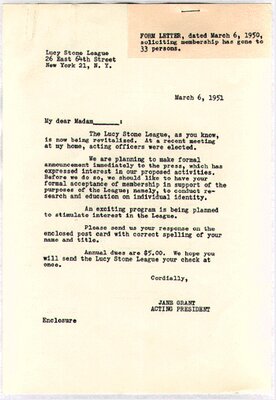

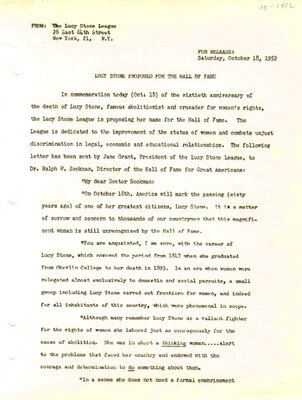

The chronological history of the Lucy Stone League remains sketchy. A letter from Hale to Grant in 1925 shows that personal differences had begun to interfere with the League's day to day operations. In a letter dated April 27, 1925 written from The Portland Hotel in Washington D.C., Hale accuses Grant of "blowing her off" and trying to take over her public relations and publicity responsibilities. No response from Grant is recorded, no League news at all until Grant initiates a meeting during the winter of 1950 to reorganize the organization. It is after this dormant period that Jane Grant was elected President of the Lucy Stone League and the fifteen women in attendance pledged to concern themselves "with all civil and social rights of women."

As the League matured, its goals and programs became more imaginative. Lending libraries honoring prestigious women were founded at elementary schools and in one case at the House of Detention for Women in New York. Scholarships were provided for young women who were pursuing studies in the traditionally male dominated fields of business, engineering and medicine. A letter from Grant to the editor of Timemagazine states that the League is trying to persuade Harvard University to admit women to their Graduate School of Business and to restore citizenship to American women who have married foreign nationals. "We have a long list of projects, most of them having to do with discrimination against sex (female). It's a long list because there are many discriminations," the letter explains.

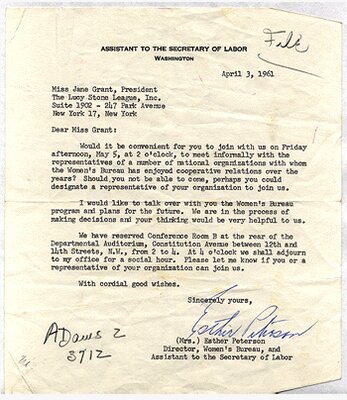

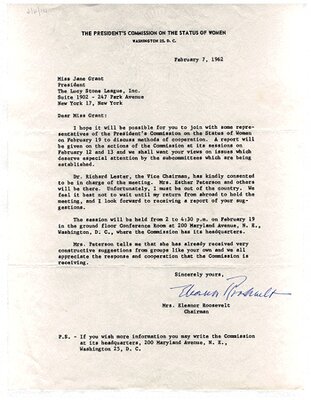

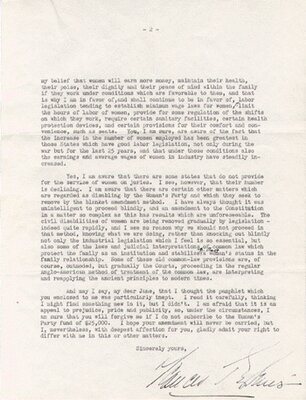

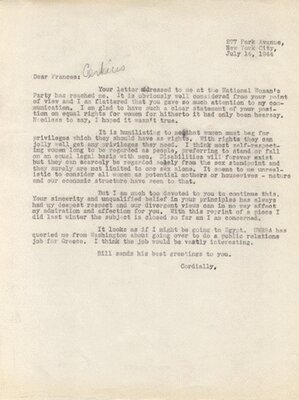

Throughout her life whenever a letter arrived at her door addressed to Mrs. Harold Ross, or later, Mrs. William Harris, Grant's response was lively, ironic, and instructive. Some of her most eloquent prose addresses the profound importance of keeping one's own name. "My name is Jane Grant. It's a good name. I've had it since a couple of minutes after I was born. It's mine. I haven't traded it for other people's names--like Ross or Harris, which are all right for Ross or Harris, but not for me. I'm Grant." Miss Grant was asked by Eleanor Roosevelt to join the President's Commission on the Status of Women in 1962. She accepted the invitation.