It Must Be Human

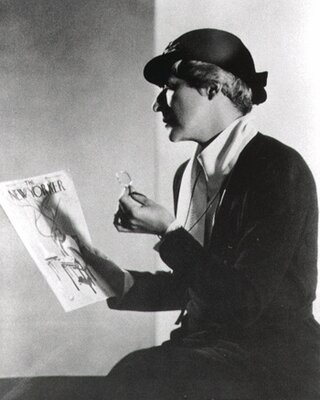

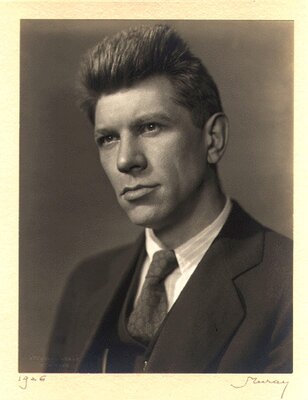

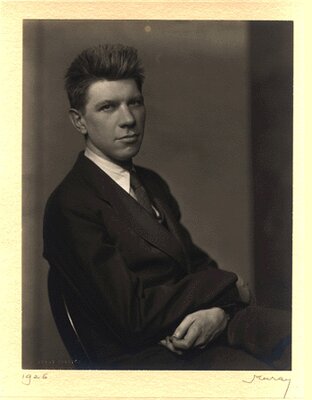

Harold Ross, founding editor of The New Yorker magazine admitted that there would be no New Yorker if not for her. And although Jane Grant never held a staff position at the magazine, she was just as integral to the magazine's initial success as was her husband, Ross. When virtually no one in New York thought the magazine had a chance of surviving beyond the first edition, it was Grant who obtained the necessary financial backing from businessman Raoul Fleischmann "She got a sucker where I failed, after a long hunt for suckers," Ross told anyone who cared to listen.

Initially, Fleischmann, good gambler that he was, told Grant he would "risk" the sum of $25,000 on the magazine. But this was only the beginning. Raoul Fleischmann was to become The New Yorker's first publisher.

From the start of Grant and Ross's married life, Grant's salary as a New York Times reporter and freelance writer supported them both; Ross's pay was held aside for the dream of a magazine. It was Grant's suggestion that they divide Ross's earnings, each investing a portion as he or she thought best. Grant played the stock market with her half and won, regularly outstripping Ross's contribution.

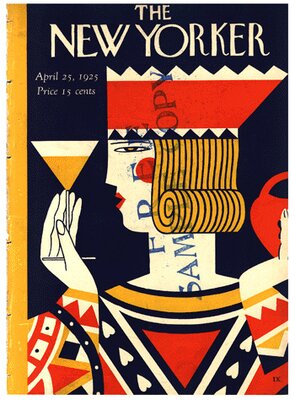

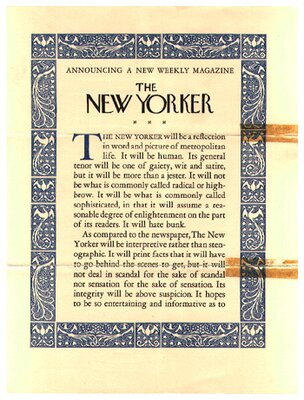

By late summer 1924, the only question left concerning the magazine was its raison d'être: a mission statement was needed as well as a name. The New Yorker prospectus, written by Ross in fits and starts is today the most famous magazine prospectus in history: 'The New Yorker' will be a reflection in word and picture of metropolitan life. It will be human.As for the name, The New Yorker, it was Round Table member John Toohey who offered the idea one day during lunch at the Algonquin Hotel. "The New Yorker"seemed to go to the core of what Ross was looking for and he showed his appreciation by offering Toohey stock in the magazine as remuneration. To Toohey, and everyone else at the table, the offer of stock in a magazine not yet on the newsstand seemed an act of terrific hubris.

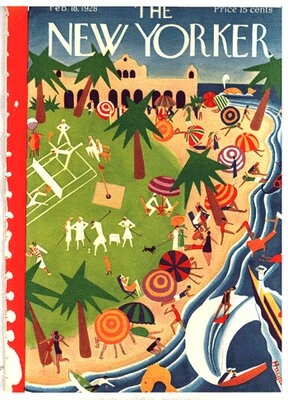

On Tuesday, February 17, 1925 the first edition of The New Yorker hit the streets. Its reception was less than welcoming. Grant's editor at The Saturday Evening Post told her he had thrown the issue across the room in disgust. From all accounts, the magazine still had a long way to go.

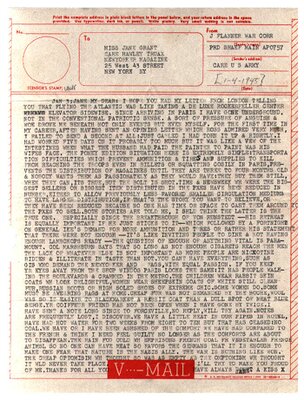

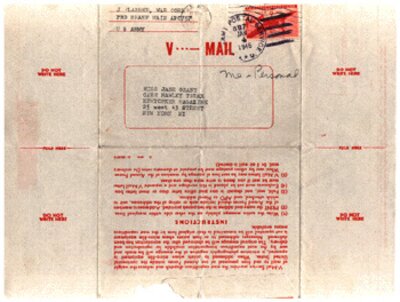

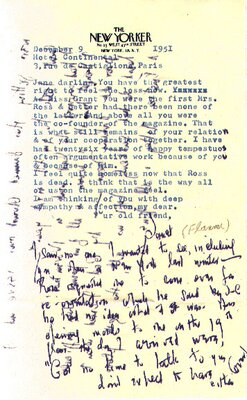

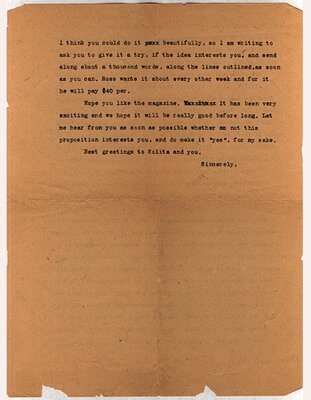

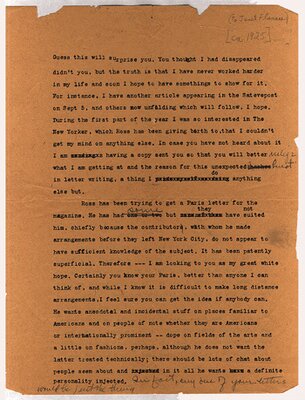

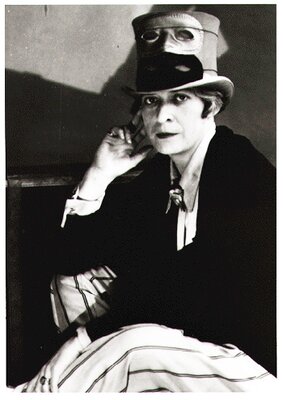

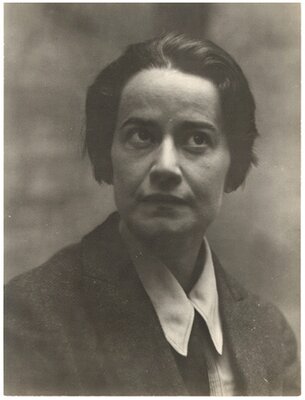

It was during the first year of the magazine that Grant asked her good friend Janet Flanner to contribute a "Paris Letter." Ross's love of Paris was still a strong hangover from his years there during World War I and he needed a correspondent who knew the city as well as he did. Flanner had moved from New York to Paris in 1921, because as she said, "I wanted beauty with a capital B." Flanner felt that the kind of life she and her lover, Solita Solano, wanted was possible only abroad. On the Left Bank, Flanner befriended Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, she knew Ernest Hemingway and Djuna Barnes. "Certainly you know your Paris better than anyone I can think of," wrote Grant encouraging her to take the job. And Flanner did, contributing her "Paris Letter" to the magazine for over fifty years. The "Letter from Europe," as it is now called, remains a standard feature of The New Yorker today.

The heartfelt friendship that existed between Grant and Flanner is evident in the letters that traveled back and forth between them over the decades. "Now I have two things which have expanded my life to thank you for," Flanner wrote to Grant "The New Yorker job and flying the Atlantic." She then went on to describe her first ride in an airplane--the remarkable sight of lifting off over New York at 2 am and arriving that same morning in London. "We flew so low to London that I could count the sheep," Flanner wrote. Her letters were filled with sharp observations and often ended with a flourish--"Love darling Jane, and thanks for my job which is still the best on earth."

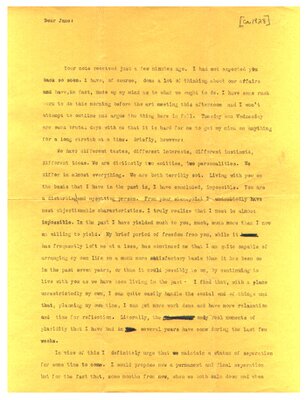

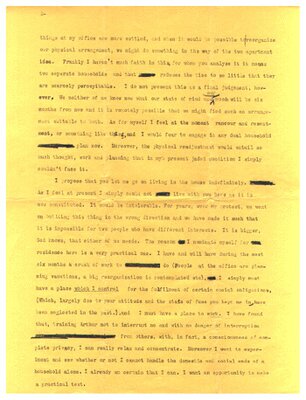

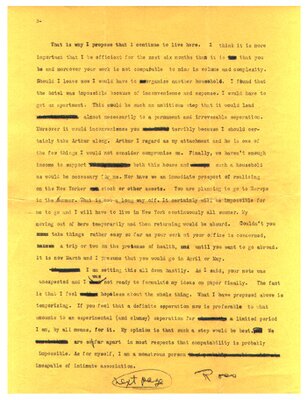

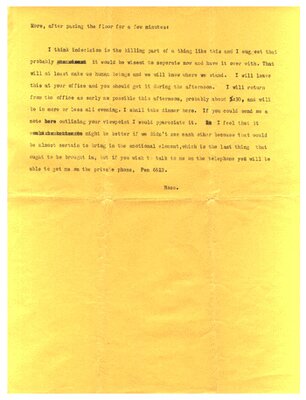

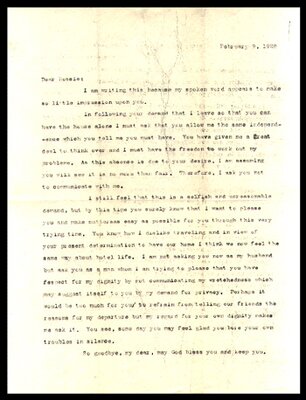

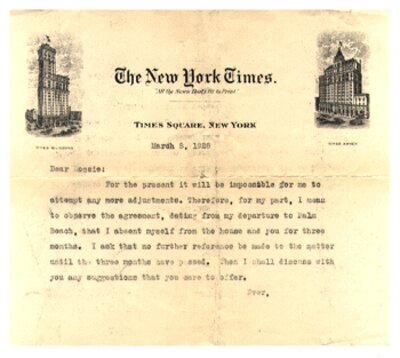

While Grant was looking out for Flanner's interests, her own life was slowly unraveling. An epidemic of divorces had broken out among The New Yorker staff during its early years--and Grant and Ross's marriage succumbed as well. Certainly, the stresses of running a weekly magazine contributed much to their personal problems. The constant socializing at #412 was not conducive to a serious work life. Ross would take his typewriter and lumber from room to room seeking a quiet spot to write. Eventually, he took rooms at The Webster Hotel across from the magazine's offices--convenient when he would work late. And soon he began staying at The Webster with more and more frequency. Finally, during the winter of 1928, Grant reluctantly agreed to a trial separation. Ross asked her to leave the city and again Grant obliged, taking extended sick leave from her job at the Times.

Upon her return, Grant filed for a legal separation. She told Ross she was against the traditional notion of alimony and instead, hit upon the idea of getting financial support from The New Yorker itself. Grant felt quite rightly that she had sacrificed a good deal for its success. Her plan was essentially a three-way agreement between herself, Ross, and The New Yorker. Ross would put shares of New Yorker stock into an escrow account for Grant and she would receive all dividends and stocks for a total of $10,000 a year. Once again, Grant proved to be astute in her business agreements and practiced in the art of survival.